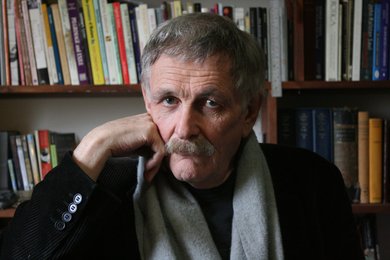

Paul Cox

6 April 1940 – 19 June 2016

See also

- alienation

- corruption

- directors

- Dutch

- immigration

- infidelity

- love

- migrants

- photography

- religion

- Second World War

- sexuality

- spirituality

Related people

- Julia Blake

- Jane Campion

- Rolf de Heer

- Gosia Dobrowolska

- John Hargreaves

- Chris Haywood

- Wendy Hughes

- Norman Kaye

- Charles Tingwell

- David Wenham

- Aden Young

Related events

Lynden Barber profiles filmmaker Paul Cox, the father of independent art cinema in Australia.

For over four decades the Melbourne-based, Dutch-born Paul Cox has ploughed a determinedly individualistic furrow to become one of Australia’s most internationally distinguished filmmakers. Well-established auteurs – filmmakers with readily recognisable personal styles and thematic obsessions – are a relative rarity in Australia. Rolf de Heer (also born in the Netherlands) and the New Zealand-born Jane Campion fall into the category, but Cox’s career predates both of theirs.

Invariably working with limited budgets, Cox has built up a large body of work and a serious international reputation as a humanistic film director, with an extensive list of international retrospectives to his credit including Telluride, Istanbul and Calcutta film festivals and New York’s Film Society of Lincoln Center. Among his most celebrated titles are his 1981 breakthrough, Lonely Hearts, and 1983 follow-up Man of Flowers (both of which achieved widespread international distribution and critical acclaim), My First Wife (1984), Cactus (1986), A Woman’s Tale (1991), his own edit of the troubled production Molokai: The Story of Father Damien (1999), Innocence (2000), and Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky (2001).

Between 1970 and 2007 Cox had been the most prolific director in Australia, making 20 features, one IMAX film, three children’s films, 10 documentaries and 12 shorts. ‘I had the right people to help me get on to the next dream’, Cox told ABC Radio National in 2009, citing a European sales agent who had consistently helped him finance his films. ‘Also I had an extraordinary passion for work. I worked all the time. Also those films were done for very little.’

Influenced by European filmmakers including Ingmar Bergman, Sergei Parajanov, Jacques Tati, René Clément, Luis Buñuel and Andrei Tarkovsky, Cox’s films have consistently explored the inner landscape of human feeling, prizing emotion over intellect. His protagonists frequently reflect his own life journey as a sensitive man who has trouble existing in a world out of joint. In Cox’s 1998 book Reflections: An Autobiographical Journey, he observed that ‘film is the very medium that can penetrate and then project one’s inner side’. Although free of special effects and expressionistic devices, his films play out not so much in the key of social realism as inner realism, achieving a heightened emotional authenticity.

In the foreword to Cox’s 2011 book, Tales From the Cancer Ward, detailing his battle against liver cancer towards the end of the preceding decade, leading US film critic Roger Ebert wrote, ‘Of all the people I have met in this life, you seem to care the most. Your fierce anger leaps out at injustice, bigotry and stupidity.’ For all that, his work is often gentle in mood and laced with a sly humour that possibly betrays the influence of his adopted home of Australia, where his filmmaking began following a career as a lecturer in photography and cinema at a Melbourne arts college.

Love, lust, organised religion versus spiritual transcendence, aging and mortality, societal corruption and shallowness, infidelity, and the pursuit of beauty and meaning in life are among the themes to which he has repeatedly returned, the latter most obviously in Vincent: The Life and Death of Vincent Van Gogh (1987), based on letters from the artist to his brother Theo, and Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky (2001), inspired by the writings of the Russian choreographer. Each of those films reflected Cox’s close, even obsessive personal identification with the struggles of those individuals as creative artists.

Cox’s protagonists are never heroes. Rather, they are flawed individuals who frequently behave irrationally in a struggle to stay afloat in a hostile world. One of the clearest examples occurs in My First Wife (1984), which is not autobiographical though it is loosely inspired by the breakdown of Cox’s own marriage. An abandoned husband (John Hargreaves) storms into the home of his wife’s parents and scorns his father-in-law’s (Charles Tingwell) admonitions to discuss his issues man-to-man, in a ‘rational’ manner.

Cox’s aesthetic approach and personal attitudes were formed in the crucible of the Second World War. Born in 1940 to Wim and Elsa Cox as one of six children, his earliest memories are of Nazi invasion. Aged four he experienced German soldiers invading the family home looking for his uncle. Later, the family was evacuated and he witnessed civilians dying from suffocation, bombing and starvation. His experiences instilled a lifelong hatred of gratuitous violence on screen.

After the war life was still bleak. Cox recalls his father appeared embittered and cold. A teacher refused to believe he had penned an essay on the sinking of the Titanic because it was too well written. An eccentric incident in which he placed his hand directly on the prominent cleavage of one of his visiting aunts is replayed in fictional form in one of the flashback sequences in Man of Flowers (1983) – one of many sequences in his work shot on the home-movie format of Super 8, in which he began making short films as a young man.

Becoming a choir boy at a Catholic church proved an influential experience. References to churches and ministers would become common in his films, particularly Molokai (1999), about a Belgian priest (David Wenham) overseeing a Hawaiian leper colony, and Man of Flowers (1983), where Norman Kaye’s protagonist played the church organ to cool down after paying to watch a young woman undress.

Cox’s father operated a film production company with his uncle, producing what Cox calls ‘semi-dramas, semi-documentaries’, and also owned a photographic business. Cox was used to having cameras and film canisters around the family home and sometimes helped his father in the darkroom. On a trip to Paris as a teenager with his mother, Cox borrowed one of his father’s cameras and quickly discovered a visual flair. This would develop when he sailed to Melbourne and stayed for 18 months on an Australian Government scheme in 1963, his motive being simply to escape his home (he had wanted to go to Sydney but the vessel terminated in the Victorian port). In 1965 he returned to Melbourne and established a photography studio. His turn towards the moving image, initially with short films, came after the Prahran College of Advanced Education, where he taught photography, launched a cinema course and he realised he had to stay one step ahead of his students.

Cox’s first three features – including his debut Illuminations (1976) and Kostas (1979) – concerned the relationships of Australians with European migrants and were little seen. His fourth feature, Lonely Hearts (1981), a touching romance between two acutely shy adults, became his first public success, with distribution in the US. Its stars, Wendy Hughes (from Kostas) and Norman Kaye (subject of Cox’s 2005 documentary, The Remarkable Mr Kaye), became regular actor collaborators, as would Chris Haywood, Julia Blake, Aden Young and Gosia Dobrowolska.

Like most filmmakers, Cox’s career has had its ups and downs. Not all of his films have been commercial or critical successes, including The Nun and the Bandit (1992), Exile (1994) and Salvation (2008). The director’s outspoken views, including his criticisms of the Australian film industry, have not always endeared him to some local critics or film executives. But having conquered cancer via a liver transplant – an experience captured in On Borrowed Time (2011), David Bradbury’s admirable documentary tribute to Cox – he appeared reinvigorated in 2011, burning with a desire to keep creating.

External Links

- Actor Chris Haywood interviews Paul Cox, Radio National

- Paul Cox: An Appreciation, Roger Ebert, Senses of Cinema

- Paul Cox – Filmmaker, essay by Philip Tyndall, Senses of Cinema

- Paul Cox, Wikipedia

- Reworking Romanticism: Paul Cox’s Man of Flowers, Victoria Duckett, Senses of Cinema

- To the point on point, Chris Haywood on working with Paul Cox, Senses of Cinema

- Vale Paul Cox, NFSA

Citations

- From the Cancer Ward (2011)

Cox, Paul

Publisher: Transit Lounge, Melbourne - Reflections: An Autobiographical Journey (1998)

Cox, Paul

Publisher: Currency Press, Sydney

- Titles

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography