Chris Haywood

24 July 1948

See also

- acting

- actors

- cultural identity

- drinking

- English migrants

- film industry

- improvisation

- mentoring

- social realism

Related people

Chris Haywood has had one of the longest careers in modern Australian film, playing a series of outsiders. He speaks to feature film curator, Paul Byrnes.

Chris Haywood is the accidental actor of Australian film. He had no great ambition to be an actor, yet his career has now spanned 40 years, during which he has appeared in many classic Aussie films. He is one of our best-loved character actors, although his infrequent lead roles have been amongst his best. He’s a perennial outsider in our movies, probably because he was not born here. Haywood is English and he retains traces of the London accent he had when he arrived in 1970. The accent was often a problem in the early days. He would turn up for auditions and the casting director would tell him the role was for an Australian. ‘I would argue quite strongly, even then, that I’m a migrant. Aren’t I Australian? This place is made up of migrants. And sometimes I would get the job, by arguing it. And so the character would develop, as a sort of Englishman who was in Australia.’

Nevertheless, he thinks it restricted the roles he was offered.

'The heroes of any country’s movies are the sort of archetypes, aren’t they? And unless you actually really fulfil that, it’s a bit difficult to become that sort of hero. And if you look at the sort of jobs I do, I’m invariably, perhaps, a character that some of the lead actors might not want to associate themselves with. It might be a communist mining leader (as he was in Strikebound, 1983) – or like in Beneath Hill 60 (2010), a soldier who breaks down totally when he has to go underground (in the trench tunnels of the Western Front). It shows his great weakness; it shows the side of a man that is perhaps not what you want to see in an Australian hero.’

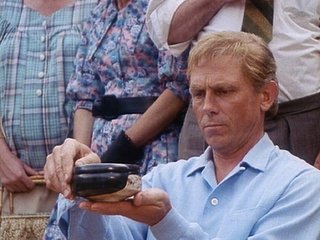

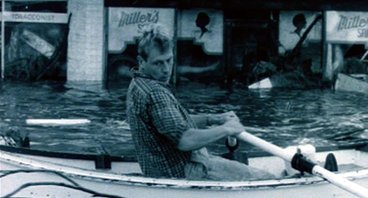

Haywood has been heroic in a number of roles – but that often means he also died. Many will still remember his tragic departure in the Maitland floods in Newsfront (1978), or as the Vietnam vet in A Street to Die (1985). The range of his roles is astonishing. Small or large, he usually does something memorable. In Malcolm (1986), he has barely a few seconds of screen time, but he makes those memorable (see clip three, Malcolm). He excels in comedy, often as a man who’s a bit confused by life or other human beings. Look at the way he reacts to Andrew S Gilbert in clip three of Kiss or Kill (1997). The timing is acute, but most of the comedy rests in Haywood’s rapidly changing emotions. Great character actors can make themselves instantly likeable on screen, but Haywood can also do the opposite. There’s a chilling coldness in some of his roles, like the killer in Jindabyne (2006).

Haywood arrived in Australia as a ‘ten pound Pom’ – a migrant under a scheme which encouraged British people to come for as little as a ₤10 airfare. He was fresh out of drama school at E15, one of the newest and most innovative schools in London. Improvisation and politics were a strong part of the school’s approach, but Haywood had applied to become an actor on a whim. He was working in a wine merchants’ in north London when a young driver told him he’d just been accepted at E15. ‘It struck me that if this bloke could be an actor, then why couldn’t I? To me actors had been some sort of demigods and matinee idols.’ He called the school that day and talked his way into an audition the following Monday. He arrived at the audition fortified with whisky, unprepared except for what he had gleaned from the driver. One of the exercises was an improvisation. They had asked the driver to pretend he was Cassius Clay (aka Muhammad Ali) making a speech in the ring. They asked Haywood to do the same thing, so he relied partly on what the other guy had done.

‘The head of the school asked me what role did I think theatre had in politics and this is where I scored, because for three years I had been chairman of the Young Liberals in the town where I lived, High Wycombe. So I just reeled off a whole lot about the applications it could be useful in. Of course, the Young Liberals in Britain are not like the Liberals here. They were not conservatives.’ The director of the school offered him a place there and then, provided he could get a grant to pay his tuition – which he did, from his local county council.

Haywood’s only experience of acting before this was in a production of The Mikado at the Royal Grammar School in High Wycombe, a school he attended on a scholarship. His academic record was patchy. ‘Once I got there, academically I just collapsed. I don’t know why. It just fell apart … Life had been a breeze up to then. For some reason, after the first year, I was not achieving. I was distracted.’ It has taken him a long time but he thinks he now understands the reason. ‘I was diagnosed [recently] with ADD which, according to the psychiatrist, I have had all my life. Which would explain a lot of things…’ He believes the decision to apply to drama school was partly symptomatic of the condition – he decided on a whim. ‘I’ve never had ambition, in that sense. I have never gone “Right, this is going to be the plan.” I have only gone, “Well, that door is open, so right, I’ll go through.” That is me. That is the ADD.’

Coming to Australia was a similar decision. Richard Wherrett, who would become one of the major Australian theatre directors of the 1970s and 1980s, was a tutor at E15 in 1969. One of the pupils was Larry Eastwood, who would become a prominent production designer in Australian film. They suggested to the young graduating actor that he come to Australia, as they were both returning there, so he did. ‘In November 1970 I got on a plane. I was met at Sydney airport, taken to Whale Beach, and I was at a party there for the next two days. I couldn’t believe it. I knew so little about Australia. My references were things like The Observer’s Book of Cars, and that only had two Australian cars in it, so I thought, “Christ, they can’t have enough vehicles out there.” I was a bit of a petrol head, and I thought, “I’ll have to buy a horse”, so I went and learned to ride before I left. Between July and November I became quite an accomplished horseman. I got off the plane thinking, “Now where do you go to buy your horse?” That eventually paid off because there were all these historical things being made and not that many actors who could ride here.’ At the Whale Beach party, he met a number of aspiring young actors, including Wendy Hughes and John Hargreaves.

He took a job as a surveyor’s assistant on the planning for the Eastern Suburbs railway, while going to theatre auditions. He did some work as an extra at Film Australia and understudied roles at the Old Tote and other Sydney theatres. Drama school in London had prepared him for anything. ‘It was an excellent school. It was life changing, it really was. It would be illegal now, what they did there. It was so confronting. They drove you to every edge of your emotions. You find emotionally where your limits are in everything – physically as well. It was totally different to the other schools, like RADA and LAMDA. The approach was much heavier and much more real. They weeded people out pretty quickly. Of the 30-something in the first year, there were 20 in the second year and 11 in the third. They got through them quickly, to see who would survive. The whole thing for me was wonderful. It was really confronting but I loved it … At the end of it I thought I could do anything, not just acting, but anything – because I knew what my limitations were. If I decided to do anything, I knew, right, I can do that much, so it means I’ve got to do that, and physically I’ve got to change to do that … It gave you that perspective.’

He was soon appearing in drama series at the ABC (such as Certain Women), cop shows at Crawford’s (including Homicide and Matlock Police), and doing plays at night. ‘There was a feeling of great energy at the time, particularly in the writing. Australia seemed to be about ten years behind England in where it was going theatrically, so the social realist movement had been going here for only a few years – (David) Williamson and (John) Romeril, (Jack) Hibberd and (Alex) Buzo were all starting to become prominent, La Mama (Theatre) was prominent in Melbourne.’

His first major film role was in The Cars That Ate Paris in 1974. This was Peter Weir’s debut feature and Haywood had a memorable role as a nurse in the psychiatric ward of a small-town hospital. He remembers that drinking was common on film sets in the ‘70s. ‘John Meillon and I would drive up from Bathurst to Sofala every morning in my old ex-Army Land Rover. At 5 or 6 am we would jump into this vehicle with a couple of other actors and soon as we were out of Bathurst, out would come the big tins of Fosters and he would have one and I would have one and we would start on the Fosters on the way to work. That was the culture. It seemed to be a lot of people’s culture then. It was grog on from the moment you started. The crews were doing it too.’

Haywood believes the drinking cost him work, because he developed a reputation for hard living. His breakthrough role came in Newsfront in 1978, where he plays the young assistant cameraman learning how to shoot newsreel stories with a senior man played by the late Bill Hunter. ‘Hunter and I lived pretty hard on that film. We really got into it. I was blacked in the industry and there was some undermining going on by two commissioners at the AFC. It had an effect on my career.’ Newsfront (1978) had been a huge hit, and his career ought to have been taking off, but times were lean for about two years afterwards. He was living with Wendy Hughes, and they had a child. Fatherhood eventually made him slow down, he says. ‘You have to be awake for your family.’

Wendy Hughes introduced him to Paul Cox while she was preparing for her role in Cox’s third feature, Kostas (1979). Cox cast him in the film as well, and that began a partnership that has been the most important in Haywood’s creative life. Haywood has appeared in 15 films by Paul Cox since 1979. He has worked on another couple uncredited, as part of Paul Cox’s extended family of co-workers. ‘On the last one (Salvation, 2008), I gaffered it, gripped it, I cooked, acted as a sort of assistant director on the set … From Kostas on, it just sort of took off and ever since I have always worked on both sides of the camera with Paul.’

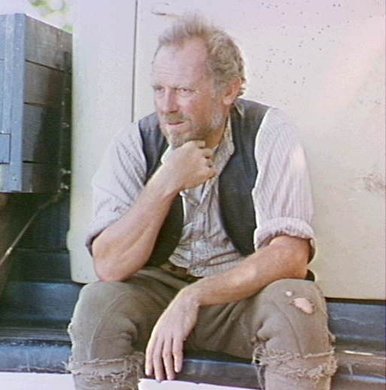

The connection may partly be explained by the fact that both men were migrants to Australia – Cox coming from the Netherlands. His films have never had a simple relationship with his adopted country and Cox has always been willing to cast Haywood in roles that stretched him. In Island (1989), shot in Greece, Haywood played a deaf-mute carpenter, one of his favorite roles. In Golden Braid (1990), one of his few leading roles, he is a quiet man who becomes obsessed with a lock of hair. In The Nun and the Bandit (1992), he’s an impoverished kidnapper of a nun played by Gosia Dobrowolska. These two were opposite each other again in A Woman’s Tale (1991), in which Haywood plays the uptight and unloving son of Sheila Florance’s Marta, an old woman facing death. That film is typical of the way Cox has often cast Haywood in an unusual role.

One of the distinguishing factors of Chris Haywood’s career has been the long-standing relationships he has had with certain directors. He has made three films with Bill Bennett – A Street to Die (1985), Kiss or Kill (1997) and The Nugget (2002). The first of these gave Haywood one of the best roles of his career, as a returned soldier trying to sue for damages over exposure to chemicals in Vietnam. He has made two films with Richard Lowenstein, Strikebound (1983) and Dogs in Space (1986), and two with Phillip Noyce, Newsfront (1978) and Heatwave (1982). His performance as the crooked but likeable developer Peter Houseman in Heatwave is one of his most interesting: again, he plays an English migrant to Australia, as he did in Newsfront. His own favourite roles include Newsfront (1978), Strikebound (1983), A Street to Die (1985) and Golden Braid (1990) – perhaps not surprising, since he had the main role in most of them.

One role that is less known, but very important to him, was the lead in Roger Scholes’s wintry Tasmanian epic, The Tale of Ruby Rose (1987).

'We were filming at the Walls of Jerusalem in Tasmania. It was a six-hour walk in to the location. We were supposed to have a helicopter to supply us but it was grounded by the weather, so when we got there, there was no food and no cook, nothing. So we were snaring and eating wallabies. There was a garden that had been created for the film and had been growing for some months. It had brussels sprouts and carrots growing, so I cut the sprouts down one side of the plant, so they could still film them, and I cut the carrots off under the ground, and left the tops. We ate brussels sprouts, carrots and wallaby for about three days before anyone came in with food. Then the weather came in even worse. The army was having their annual winter manoeuvres in the next valley and they pulled out. It was phenomenal, but it was such a beautiful and haunting film. No-one even thought of cutting out.’

Haywood is now a youthful 63, and he continues to work as much as he can. ‘I do everything I can. [In 2008] I played Big Daddy on stage in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in Melbourne. That is the biggest theatre role I’ve ever played.’ He prefers to work in film, but he is sanguine about the state of the industry, and outspoken about the lack of support for actors. ‘We are supposed to represent Australia in a sense, in the films, and we are treated like shit, quite honestly … I think that the support of the arts is abysmal. Specifically, with regard to actors on film, the budgets here are getting smaller and smaller… Actors’ money has gone down and down. Everything is done as a minimum … It is half what it used to be.’

He regards himself as very fortunate to have been able to make a living as an actor for almost all of his career. ‘Yes, I’ve had a great career and I’m very grateful for that success. Perhaps it could have been better if I had had a higher profile, but I think I have had an unbelievably privileged life. I don’t regret the times I am not working because I have had that time with my children. Probably the greatest gift to man is that time.’

'What I was saying to the AFC 20 years ago has proved to be absolutely right, that it’s the marquee value of the actors that enables you to sell your film outside Australia. You’ve got to develop a profile of those actors … On the other hand I came from England to here and even now, every day just about, I am very happy being here. This is such a unique country. But I’m also very angry that there is not enough pride in our industry to promote us as we are. Why do we need to go overseas to create the career? Why can’t our careers here be enough, with the proper support of the industry, to develop an international profile? Why do we need to work outside? We shouldn’t have to. It’s so ridiculous. The naivety, the naivety of governments in this country, to not recognise what an impact a national film industry has…’

Haywood now finds himself mentoring younger actors – about technique, their careers, and working with directors and how to demand what they need to do their best work. ‘Thirty years ago there was this core of older actors around who had had a film career right through, some of them, from the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s – Charles Tingwell, John Meillon, Ray Barrett, John Ewart – they had an understanding of filmmaking. (John) Hargreaves had his mentoring from Meillon. And there was more of that then because they were the core of the industry, in a sense.’

The fact that Haywood is an actor may be accidental, but not the fact that he’s such a good one.

External Links

- Titles

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography