The Depression

The Great Depression is everywhere and nowhere in our cinema. For an event that had such a cataclysmic impact on the country, there are very few direct signs of it in the films made between 1929 and 1932, the worst years (in fact, there are very few films made at all in those years). On the other hand, there are many signs in the films made much later. Phar Lap (1983) and Bodyline (1984) are both about the Depression, just as much as they are about a horse or a test cricket series. The events they portray were magnified by the social circumstances.

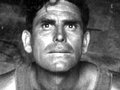

The Shiralee (1957) is partly a Depression movie because it’s based on D’Arcy Niland’s experiences as an itinerant labourer during the Depression. The Sundowners (1960) is similarly informed by what the writer Jon Cleary knew of his family’s life in the bush in the late 1920s. An actor such as Chips Rafferty embodied for postwar Australians a sense of resilience and hope, and a great spirit of adaptability. Rafferty too was a product of the Depression, during which he moved from job to job, taking what work he could find. In a sense, he’s the hero we wanted to see after surviving the Depression and the war – a new kind of lanky, independent Australian who was home-grown and toughened by hardship. There are signs too in the new radicalism of the post-war period, in films by the Realist Film Unit and the Waterside Workers’ Federation Film Unit. The Depression’s effects are said to have been worse in Australia than in most other countries – and that may be why no-one wanted to talk about it, or see movies about it. The Depression was depressing.

The films of the 1930s, dominated by the commercial imperatives of Cinesound Productions, generally avoided even mentioning the Depression, but it’s there in the thinking behind most of Ken G Hall’s decisions as the driving creative force of the studio. We see it in the films he chose to make, and the way he made them. Cinesound’s films championed battlers, both rural and urban; they identified with the little man against the wealthy and powerful establishment; they often featured stories in which riches came to men in rags, because audiences desperately wanted to believe it could happen. After The Broken Melody in late 1937, the last time he tried to deal with the effects of the Depression, Ken Hall concentrated solely on making comedies, because he believed that was what audiences wanted.

The Depression played a big part in all of these decisions. There were hard times aplenty, right from the first Cinesound feature, On Our Selection (1932), but no-one mentioned the ‘D’ word. In clip one of that film, the Rudds are about to lose their cattle to Old Carey (Len Budrick) but it’s because of drought, not the Depression. The film was made in 1932, the worst year of the Depression, when unemployment in Australia reached 29 per cent, second only to Germany. Bert Bailey’s speech in clip one is not just about farming. It’s a pep talk to the nation and a reminder that times will improve. Carey is about to seize his cattle – what will you do, he asks old man Rudd. ‘Do? What the men of this country, with health, strength and determination, are always doing – I can start again!’

Bailey gave similarly rousing speeches in several Cinesound films. He exploits popular sentiment against the wealthy and the powerful in clip two of Dad Rudd, MP, where he announces his intention to run for parliament. This film was made in 1940, several years after the Depression was officially over, but this sense of anger at poor political leadership – especially from Great Britain as the ‘mother country’ – was very strong in Australia, partly as a result of events during the Depression, when British banks refused to finance further loans to the Australian government.

That anger surfaces in all sorts of ways, in all sorts of places. Cricket is an example. The English cricket team toured Australia in the summer of 1932–33, the famous Bodyline series. Australian crowds were incensed at the tactics of bowling fast at the body, and pitching short balls at the head of Don Bradman. In some Labor-voting circles, that anger was mixed with strong political rage after the sacking of NSW Premier Jack Lang in May 1932. Lang had proposed to repudiate the debt owed to foreign banks, most of which were British. Lang’s opposition to the ‘Melbourne Agreement’ of 1930 eventually brought down the federal Labor government of Prime Minister James Scullin in late 1931. The Bank of England was widely seen on the left of Australian politics as dictating economic policy to Australian governments. The thrust of these policies was to slash government spending, despite the hardship this caused. Lang wanted to spend more money to stimulate the economy; he was sacked by the NSW governor, Sir Philip Game, in May 1932, six months before the English team arrived to contest the Bodyline series.

After a year of the most tumultuous political events, we may reasonably assume that many in the crowds at the tests in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane were angry about more than Douglas Jardine’s tactics as English captain (see clips one, two and three of Bodyline, 1984, for a discussion of those tactics). Australian newsreels covered many of these events as they happened. We have clips of three of the five tests in the Bodyline series:

1) Australasian Gazette – Highlights of the Cricket Series England vs Australia (1933);

2) Australasian Gazette – Historic Cricket (1933, second test in Melbourne);

3) Australasian Gazette – The Ups and Downs of Cricket (1933, third test).

See also That’s Cricket, a Cinesound documentary on the central place of cricket in the country’s national psyche, made in 1931 (before Bodyline). Jack Lang appears in clip two of The Opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1932). James Scullin is shown attending the ALP’s Easter Conference in Melbourne in early 1928, when he was still deputy leader of the federal Labor Party (see Delegates to the Australian Labor Party’s Easter Conference at the Trades Hall Melbourne, 1928, clip two). This was shot before the Depression began. Scullin became Prime Minister a few days before the crash of the New York stock exchange in October 1929.

Australian newsreel production expanded during the Depression, largely because of the coming of sound-on-film technology from the US. Audiences flocked to see Fox Movietone News and its rivals Cinesound Review, Paramount News and (in Melbourne) the Herald Newsreel, but not for coverage of the economic hardships of the time. ‘As evictions increased and people roamed in search of work, unemployment camps sprang into existence around most Australian cities and large towns’, write film historians Graham Shirley and Brian Adams in their book Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (1989, Currency Press, Sydney, p 108). ‘Newspaper photographs showed the shanties, the cave homes, the relief and charity work, and confrontations with police. In providing entertainment that would allow their audiences a brief respite from these events, the Australian newsreels completely ignored them.’

The coming of sound and the economic crash almost completely destroyed live theatre, especially vaudeville, in Australia. Thousands of actors and theatre musicians joined the unemployed lines, but audiences in 1929 still went to the cinema, largely because ‘talkies’ were new and tickets were cheap. This did not last. By mid 1931, film returns hit a five-year low and several exhibitors experienced significant losses. In October 1931, Stuart Doyle’s Union Theatres reported a loss of ₤100,000 and went into liquidation. Doyle had already announced two years earlier that he was setting up an Australian film production arm. This was in December 1929, two months after the crash. The losses at Union Theatres made this more urgent. Doyle set up a new company, Greater Union Theatres Ltd, to purchase the ₤400,000 overdraft of Union Theatres. Cinesound was thus not just born in the Depression, but partly because of it. Cinesound’s films were meant to save the parent company, in a desperate roll of the dice – and they did. That was a remarkable gamble, given the times and the relative inexperience of Ken G Hall, the man Doyle picked to direct the movies (see portrait of Ken G Hall).

Cinesound had a remarkable run of success from 1932 to 1940, when production ceased because of the war. Hall made 16 features in nine years, and only one of them was slow to break even. That was Strike Me Lucky (1934), the film debut of the popular comedian Roy Rene (aka ‘Mo’). More significantly, it was the first film in which Hall tried to set a story in the current Depression. Rene plays a man so skint that he picks up other people’s discarded cigarette butts (see clip one). Most of the film is about money, and the difference between the haves and have-nots. Hall attempts to show the degradation of the destitute man in clip three, where Rene brings a lost child home to her rich parents. As he offers Miriam’s father his last ten shillings, everyone laughs. They brush their sleeves as he passes, as if the poverty might be catching.

Whether the film failed because Roy Rene’s comedy was not suited to film, or because audiences were in no mood to see their own hard times on screen, is impossible to say, but it’s clear that Ken Hall learned a lesson. He stayed away from depictions of the Depression until four years later when conditions had improved. The Broken Melody (1938) offers a more complex view of the Depression – not that it mentions the word. A high-born man hits hard times after he’s thrown out of university. He ends up living in a cave with other homeless people in Woolloomooloo, beside Sydney Harbour (see clip two). His musical ability saves his life.

The depiction of the faces of the men at the beginning of this clip shows the influence of American directors such as Frank Capra, who tackled the Depression earlier and much more directly in Hollywood films such as It Happened One Night (1934) and American Madness (1932). Hollywood’s output in the worst years of the Depression was much more prepared to admit stories of the current hardship than anything being produced in Australia. The reasons were simple: almost no-one in Australia could afford to finance feature films, except Cinesound in Sydney and FW Thring in Melbourne. Neither was really prepared to take the risks of challenging audiences looking for respite in their entertainment. When Hall did try to extend the subject matter to current events, audiences stayed away (at least in comparison to Cinesound’s three films before Strike Me Lucky, 1934).

Depictions of the Depression became only slightly more common after the worst was over. Rupert Kathner and his partner Alma Brooks made a series of newsreels under the title Australia Today. These were much more sensationalist than any of the other newsreels in circulation. Kathner covered drug smuggling (Australia Today – Customs Officers Fight Against Drugs, 1938), murder (Australia Today – The 'Pyjama Girl’ Murder Case, 1939), sharks (Australia Today – Man-Eater, 1939) and Nazis under the bed (Australia Today – Australia’s 5th Column, 1941). In Australia Today – Men of Tomorrow (1939), Kathner and Brooks tackled the residual poverty left behind by the Depression, ‘that deadly five years which annihilated hope and ambition in so many of us’. We see slum areas where innocent children are ‘doomed from the outset’. The interiors are re-creations, with Alma Brooks playing the wife, but the exteriors give us some short glimpses of real slum areas of Sydney.

Documentary makers have later found still photographs of the lives that people led in the early ’30s, in temporary camps (see Footy The La Perouse Way, 2006, clip one). This clip is about the foundations of an Aboriginal football team, but it shows still photos of Aboriginal dwellings on the beach at La Perouse, on the northern tip of Botany Bay. In clip two of Bread and Dripping, a documentary from 1981, Eileen Pittman talks about the shanty town at Maroubra which became known as ‘Happy Valley’. She explains that the Depression was even harder for Aboriginal Australians, who were not allowed to get the dole. They were given rations instead.

The older footage used under the song in this clip comes from A Brief Survey of the Activities of the Brisbane City Mission, a film made in c1939 to highlight the work of the Brisbane City Mission. That film shows scenes from Brisbane, although the footage may be earlier, given the equipment that was used (the speeded-up movement indicates a silent-era camera). The scenes of men fighting for food parcels may be partial re-creation, or at least ‘guided’ actuality, but the grim housing and even grimmer faces of hungry men are fairly convincing.

The Depression, in its technical definition, ran from 1929 to 1932, but in terms of hardship, it continued much longer in Australia. Responses were different in different states. Beautiful Melbourne (1947), an ironic title, shows children living in terrible squalor in the inner city in 1947. Victoria’s housing shortage was still acute in the postwar years. This film was made for the Brotherhood of St Laurence by the Realist Film Unit. Father Gerard Tucker commissioned three films from the unit, which was established in 1945 with support from the Communist Party of Australia. The films were toured around Victoria with Fr Tucker delivering a narration designed to embarrass the state government into doing more for the badly-housed poor.

This alliance of communist and Catholic was highly unusual, but one of the legacies of the Depression and the Second World War was a rise in radicalism. Part of that was recognition that film could be used as a tool of activism. The Waterside Workers’ Federation started its own film unit to agitate for better pay and conditions on the wharves. In clip two of The Hungry Miles (1955), we see a re-creation of the Depression years which includes the footage of poor Sydney housing later used in films such as Bread and Dripping (1981). Clip three of The Hungry Miles (1955) dramatises violent demonstrations during the Depression years. Some of this footage looks real – the shot of police and demonstrators clashing in a city street, with one man sticking up above the others, in particular – although it may simply be evidence of how accomplished the re-creation scenes are in these films.

Even in the 1970s, when our films began seriously to explore our history, there are few films set in the Depression. One of the most popular is Caddie (1976), which tells the true story of a Sydney barmaid from about 1925 to 1932. Clip one gives a vivid idea of the reality of drinking under the 6 pm closing laws, which were in place all through the ‘30s. Clip three depicts the lengths that people went to in search of work during the Depression. These three minutes are still amongst the most powerful re-creations of the Depression in any Australian film. Caddie was produced by Anthony Buckley, who later produced two significant mini-series based on books by Ruth Park, Harp in the South (1986) and Poor Man’s Orange (1987). Though set in the postwar period, both give a memorable picture of life in a poor Irish Catholic family in the inner city. In a sense, they show a family in which the Depression never stopped.

Palace of Dreams, made as a ten-part mini-series in 1985, is set in a Depression-era pub run by Russian-Jewish immigrants. Clip one takes a swipe at the meagre charity handed out by the rich and titled – in this case, the governor’s wife, who organises breakfast for homeless men sleeping rough in The Domain, Sydney.

The desperate scenes at the beginning of the clip were used in The Hungry Miles (1955), and are probably re-creation. As often happens, the ‘reality’ of re-created footage becomes obscured in subsequent usage. Scenes that were fake to begin with later become ‘real’. In the case of the Great Depression, that’s partly because there’s so little actuality to begin with.

Citations

- Directed by Ken G. Hall: autobiography of an Australian film-maker (1977)

Hall, Ken G

Publisher: Melbourne : Lansdowne Press ISBN 0701806702 - KG Hall corrects impressions created by interview of Bill Shepherd in Cinema Papers, December 1974 (1975)

Hall, KG

Cinema Papers, No. 5, pp 46-49, 90 - Australian film, 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production (1998)

Pike, Andrew and Ross Cooper

Melbourne: Oxford University Press ISBN 0195507843 - Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (1989)

Shirley, Graham and Brian Adams

Sydney: Currency Press ISBN 0868192325 - Theatre in Australia (1978)

West, John

Publisher: Cassell Australia ISBN 0726992666

Titles in this collection

Australasian Gazette – Highlights of the Cricket Series England vs Australia 1933

This Australasian Gazette newsreel footage features highlights of the first test in the 1932–1933 England versus Australia cricket series.

Australasian Gazette – Historic Cricket 1933

This newsreel shows highlights of the second Test in the 1932–1933 series, which was won by Australia.

Australasian Gazette – The Ups and Downs of Cricket 1933

This newsreel shows highlights of the third Test cricket series – the notorious 'Bodyline’ series – between England and Australia in Adelaide in January 1933.

Australia Today – Australia’s 5th Column 1941

According to this newsreel, Australia is at war with the '5th Column’, threatened by a ruthless enemy whose objective is the 'downfall of the British Empire’.

Australia Today – Customs Officers Fight Against Drugs 1938

Stories in this Australia Today newsreel cover topics like illegal drug importation and crime syndicates; and SP bookmaking and gambling.

Australia Today – Man-Eater 1939

Shark attacks on populated beaches are statistically not that common in Australia, but they attract sensational media coverage of the type seen in this newsreel.

Australia Today – Men of Tomorrow 1939

Depicting the family life of a young boy in the poorer suburbs of Sydney, this newsreel touches on society’s responsibility to offer its youth a better future.

Australia Today – The ‘Pyjama Girl’ Murder Case 1939

This newsreel reconstructs the coronial inquest into the Pyjama Girl mystery, one of the most baffling unsolved murder cases in Australian criminal history.

Beautiful Melbourne 1947

This film, put together by the Brotherhood of St Laurence in 1947, increased public awareness of the dire state of those living in slum housing in Melbourne.

Bodyline 1984

This mini-series recreates the 1932-33 cricket test series that threatened ties between Australia and England and changed cricket forever.

Bread and Dripping 1981

Four women recall raising families during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The film also looks at the activism of women and the beginnings of the early feminist movement in Australia.

A Brief Survey of the Activities of the Brisbane City Mission c1939

This is a moving portrait of the charity work of the Brisbane City Mission for the poor at a time when many people struggled financially because of the Depression.

The Broken Melody 1938

A film with music rather than a musical, The Broken Melody is one of the few films of the 1930s that tries to depict the Depression’s effect on real people.

Caddie 1976

Caddie is a powerfully emotional statement of the ways in which women outside marriage were socially and economically disadvantaged in the period between the wars.

Dad Rudd, MP 1940

Dad Rudd, MP truly signals the end of an era, the last gasp of the cycle of rural comedies featuring yokels and livestock that went back 30 years in Australian cinema.

Delegates to the Australian Labor Party’s Easter Conference at the Trades Hall Melbourne 1928

This is rare footage of key historical figures of the ALP and trade union movement at a 1928 conference at Melbourne Trades Hall.

Footy The La Perouse Way 2006

Sydney’s La Perouse had an all-black football team in the 1930s but all nationalities were being welcomed by the 1950s.

Harp in the South 1986

The ‘harp in the south’ refers to Irish immigrants in Australia. A mini-series, based on Ruth Park’s book, follows the Darcys in the aftermath of the Second World War.

The Hungry Miles 1955

The Hungry Miles covers more historical ground than the WWF Film Unit’s earlier works and they regarded it as one of their most significant accomplishments.

On Our Selection 1932

This film was technically innovative and, when it opened in 1932, a box office sensation, rejuvenating the local film industry.

The Opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge 1932

This newsreel footage with on-the-spot commentary contains unique coverage of the official opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge on Saturday 19 March 1932.

Palace of Dreams 1985

In this acclaimed drama series, an aspiring writer arrives in Sydney from the country during the turbulent and desperate times of the Great Depression.

Phar Lap 1983

The film is well constructed, both as a folkloric tale of a young man’s bond with a special horse and as an exciting spectacle with a couple of magically charged moments.

Poor Man’s Orange 1987

Harp in the South was so admired by Network Ten’s then head of drama, Valerie Hardy, that she immediately commissioned this second series.

The Shiralee 1957

Arguably there are two major themes in Australian cinema – the problem of the landscape, and the related problem of masculinity – and both are the subject of The Shiralee.

Strike Me Lucky 1934

The Holocaust made vaudeville star Roy Rene’s Jewish caricatures unacceptable in later years, but this wasn’t the case in 1934.

The Sundowners 1960

The Sundowners is remarkable for the number of Australian actors it showcases. Chips Rafferty plays Quinlan, the contractor at an outback shearing station.

That’s Cricket c1931

A featurette directed by Ken G Hall promoting cricket as the game that 'helps unite the Empire’ and is important to Australian identity.