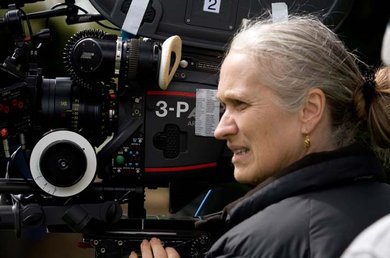

Jane Campion

30 April 1954

See also

- Academy Awards

- adaptations

- AFTRS

- Australian film

- 'Cannes Film Festival'

- careers

- directors

- female careers

- feminism

- film festivals

- New Zealand

- short films

- television

- writers

Related people

- Gillian Armstrong

- Jan Chapman

- Abbie Cornish

- Kerry Fox

- Holly Hunter

- Harvey Keitel

- Gerard Lee

- Geneviève Lemon

- Sam Neill

- Ben Whishaw

- Kate Winslet

Related events

Richard Kuipers profiles Jane Campion, whose bold and unconventional work has been acclaimed around the world.

‘I have no fear, I don’t think “Oh, this is going to flop, this is going to be horrible”, I just don’t even think about it. You just need one degree more inspiration than fear.’

Jane Campion, Strange and Strong

Born into an artistic family in Wellington, New Zealand in 1954, Jane Campion is one of the most successful and highly acclaimed of all female filmmakers. Her many awards include an Oscar, two Palmes d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, the Grand Jury prize at the Venice Film Festival and five AFI awards.

Her filmography encompasses low-budget dramas made in Australia (Sweetie, 1989) and New Zealand (An Angel at My Table, 1990); prestige international period pieces (The Piano, 1993; The Portrait of A Lady, 1996; Bright Star, 2009) and the contemporary US-shot erotic thriller In the Cut (2003).

Early career

After graduating from Victoria University of Wellington with a BA in Anthropology, Campion relocated to Sydney where she attended Sydney College of the Arts and, most significantly, the prestigious Australian Film Television and Radio School. Her arrival in Australia coincided with a determined effort by Australian educational institutions and government funding agencies to promote career paths for women in film and support the telling of stories from female perspectives.

Campion’s career rise coincides with that of several important Australasian female directors such as Gillian Armstrong (My Brilliant Career, 1979) and producers including Jan Chapman, with whom Campion first collaborated on the ABC TV series Dancing Daze (1986) and telemovie Two Friends (1987). With The Piano (1993), Holy Smoke (1999) and Bright Star (2009) to their credit, the Campion-Chapman partnership is one of the most significant in contemporary Australian cinema.

Predominantly concerned with female characters struggling to be heard, recognised and understood, Campion’s distinctive work cannot be easily categorised; it occupies the space between art house and commercial filmmaking. Her output to date is relatively small, comprising seven full-length features, a few made-for-TV projects and a handful of shorts since her 1982 debut An Exercise in Discipline: Peel (or simply Peel) won the Palme d’Or at Cannes for Best Short Film.

This tightly controlled nine-minute drama about a small event escalating into a heated family argument shows Campion’s interest in peeling away the external layers of characters and exploring what lies beneath. It is her focused interest in female characters in male-dominated societies that has produced a memorable string of protagonists whose thoughts and actions frequently rail against the status quo and challenge audiences’ attitudes toward sexual politics.

When I think of what’s fantastic about women, it’s their generosity, their intuitiveness, their capacity to trust emotions, to be emotional, to nurture, to promote peace, to care about the planet’s environment so their children can inherit it. Those qualities aren’t sexy for guys, but (they’re) quite natural in women.

Jane Campion, Strange and Strong

Triumph at Cannes

Campion’s intentions were boldly announced in her debut feature, Sweetie (1989), starring Genevieve Lemon as the mentally unbalanced daughter of a dysfunctional family whose behaviour has a profound effect on all those around her.

Screened in competition at Cannes (it was booed by some viewers and enthusiastically embraced by others), Sweetie provided the springboard to greater success the following year with An Angel at My Table (1990), a feature version of the three-part mini-series made for New Zealand television.

A portrait of the extremely difficult life of celebrated New Zealand author Janet Frame (1924–2004), it won the Grand Jury Prize in Venice. Superbly played by Kerry Fox, Frame is a great Campion heroine: a woman harshly committed to a psychiatric institution for eight years who eventually triumphs over the enormous obstacles facing her as both a woman and an artist.

Campion’s next film, The Piano (1993), is her greatest all-round success. Centred on a mute woman and her young daughter arriving in 1850s New Zealand for an arranged marriage, its combination of inspirational heroine (played by Holly Hunter in an Oscar-winning role), highly unusual locale and striking depiction of love, lust and desire in a colony of Victorian-era Great Britain, attracted mainstream audiences in large numbers and drew universal and frequently rapturous critical approval. With it, Campion became the first female director to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes, sharing the prize with Chinese filmmaker Chen Kaige for Farewell My Concubine (1993). The Piano cemented the reputations of both Campion and Chapman, and opened the door for both to acquire financial backing for future projects from French and other international sources.

Following The Piano

Campion’s idiosyncratic approach to storytelling was strikingly displayed in her next feature, an adaptation of Henry James’s 1881 novel The Portrait of a Lady (1996). Radically departing from the conservative formality of Merchant Ivory period pieces that were hugely popular at the time (such as Howards End, 1992; and The Remains of the Day, 1993), The Portrait of a Lady opens with images of contemporary Australian teenage girls and young women talking about their feelings in that tiny moment before lips become sealed in a kiss.

From there the camera cuts to a close-up of the clearly distressed face of James’s protagonist, Isabel Archer (Nicole Kidman), a young American woman in England who is vulnerable to the manipulations of female friends and male suitors. For this scene, an erotic dream sequence and other departures from James’s text, the movie was negatively received in some quarters and did not perform as well at the box office as might have been expected from the director of The Piano (1993). Whatever its difficulties may have been for viewers expecting a completely faithful adaptation, The Portrait of a Lady (1996) delivers a compelling study of a free-thinking woman whose determination to remain single – 'free’ – as long as possible is undone by the social and familial forces of conformity.

Those same forces are at work in the contemporary Australian setting of Holy Smoke (1999), starring Kate Winslet as Ruth, a young woman who undergoes a radical spiritual transformation in India and returns to her shocked and bewildered suburban family. Believing their daughter has been brainwashed, Ruth’s family hire American professional PJ Waters (Harvey Keitel), a specialist in deprogramming people from religious cults, who takes Ruth to a remote outback location for his brand of therapy.

Very much like Ada in The Piano (1993) and Isabel in The Portrait of a Lady (1996), Ruth is being punished for not fitting in to the accepted scheme of things. Like Janet Frame she is considered hysterical and mentally unbalanced and needs civilised ‘normal’ society to restore her wellbeing.

Complex, strong women

One of the most intriguing elements running through Campion’s work is how her portraits of women in distress or under duress are never simply the case of downtrodden female victims being brutalised or oppressed by uncaring men and family members. The overwhelming majority of her heroines are complex, flawed individuals whose strivings to discover and express their individuality put them at odds with the world around them.

On the flip side of this very equation is Campion’s ability to create male characters such as Waters in Holy Smoke (1999) and Alisdair Stewart (Sam Neill) in The Piano (1993) that are much more than one-dimensional figures of authority and oppression; they are fascinating men struggling to comprehend and accept what goes on in a woman’s mind.

Campion’s exploration of female consciousness was very boldly expressed in In the Cut (2003), an adaptation of Susanna Moore’s psychosexual thriller starring Meg Ryan as Frannie Avery, a New York literary professor involved in a murder mystery and engaged in a torrid affair with rough-trade cop James Malloy (Mark Ruffalo). As close as Campion has come to making a mainstream contemporary genre film, it retains her distinct focus on female desire.

Following the mixed reception to In the Cut (2003), Campion directed a segment for the omnibus project To Each His Own (2007), and made the short film The Water Diary (2006) before returning to features with Bright Star (2009), a chronicle of the love affair between tragic romantic poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw) and his neighbour, Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish).

On top

Containing some of the most ravishing images in any Campion film, Bright Star again deviates significantly from conventional biographies and period pieces. By showing the commonplace aspects of early nineteenth century English life and choosing not to indulge in staples such as the deathbed scene featured in almost every movie about an artist who died young, Campion creates a highly realistic and deeply moving portrait of a man and woman whose aching desire for each other is ultimately no match for the social and economic realities of the world into which they are born.

As with much of her work, Bright Star attracted widespread critical acclaim but its deliberately measured tempo and refusal to press easy and familiar emotional buttons restricted its wider commercial appeal. This is one of the defining characteristics of Jane Campion’s work: the surface look of a traditional thriller, love story, domestic drama, biography or adaptation of a literary classic that takes the long way around the psyche of its central characters and dares to detour into unexpected and highly stimulating territory that will not always meet with universal appeal.

Jane Campion is a mentor for female filmmakers (including Julia Leigh: Sleeping Beauty, 2011; and Christina Andreef: Soft Fruit, 1999) and has become a filmmaker whose new work qualifies as an ‘event picture’ by the very opposite criteria applied to Hollywood blockbusters. Her latest project was co-directing (with Garth Davis) Top of the Lake (2013), an internationally financed TV mini-series filmed in New Zealand.

Top of the Lake marks a reunion with Campion’s Sweetie (1989) and Passionless Moments (1983) co-writer Gerard Lee, and The Piano’s (1993) Holly Hunter. With Elisabeth Moss playing a typically complex and compelling Campion heroine – a detective investigating the disappearance of a pregnant 12-year-old girl – Top of the Lake is one of the most acclaimed television events of 2013.

Top of the Lake premiered on Australian television on 24 March 2013 and was released on DVD in Australia on 28 August 2013.

- Titles

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography