Stone Forever (1999)

Synopsis

For Stone Forever, the director Richard Kuipers interviews many of the original Stone (1974) cast and films the 25th anniversary of the film in 1998. The filmmaker makes extensive use of the rich sources of stills, black-and-white footage from the The Making of ‘Stone’ shot in 1972 and the colour footage from Stone (1974).

Stone Forever is more than a ‘making of’ documentary about the ‘cult’ exploitation feature. It uses a contemporary event as the reason to revisit Stone (1974) and discuss how it actually got made. But it also follows up the way the film was received, how the crew and actors became involved in the film and what has happened to them since.

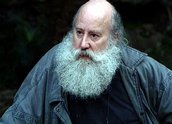

Stone (1974) was co-written, directed, produced and designed by Sandy Harbutt, who also played a major role in the film. Stone (1974) is a murder mystery about an undercover cop who wheedles his way into a biker gang, the GraveDiggers, after one of them witnesses a politically motivated assassination. Gang members are starting to be killed off one by one. The bikies are outcasts, Vietnam vets and outlaws, and cops are anathema to them.

The day after the launch, Stone (1974) was slammed by the newspaper critics but picked up by Greater Union to screen in cinemas to huge audiences. The filmmakers say that it has become one of the most profitable and popular Australian feature films of all times.

Curator’s notes

In the opening scene of Stone Forever a scroll explains that the documentary is ‘the story of Stone (1974) and those who keep the spirit alive’. It is a tribute to the film and the filmmakers that over 30,000 bikers turned up for its 25th anniversary (called ‘Run and Rage’) in 1998 to celebrate the making of Stone (1974) and recreate the funeral scene. Ten thousand of those bikers stayed on for the 24-hour party afterwards. The ‘spirit’ of Stone (1974) definitely lives on and that certainly comes across in Stone Forever.

When director Richard Kuipers was a teenager in the late 70s, the most famous Australian film was the ‘R’ rated Stone (1974). Kuipers recalls that although it seemed to be always playing somewhere he didn’t get a chance to see it until 1980 when it aired in a modified form for television on Channel 7 (without the final sequence, which actually tied the whole film together, and the infamous decapitation scene). In 1994 he was finally able to see the film uncut when it was released for Stone’s 20th anniversary and met executive producer David Hannay and director Sandy Harbutt. At that meeting, Kuipers suggested that they round up the GraveDiggers for a story on the film for The Movie Show, which Kuipers was by then producing.

Four years later, Hannay contacted Kuipers about the 25th anniversary run happening in December 1998, raising the idea of making a documentary. Kuipers jumped at the chance. He wanted to explore the incredible following the film built after having had such scathing and critical reviews, why Sandy Harbutt never directed another film and how Stone (1974) fits into Australian cinema history.

Stone Forever came into being with help from SBS, Margaret Pomeranz and Spectrum Films. Garnering a lot of in-kind support through Stone’s loyal following, Kuipers was able to get stock footage, music rights and camping gear at very low cost. Actors and crew from the film were only too happy to be interviewed.

Stone (1974) was made at the start of the revival of the Australian film industry. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) originated around the same time and both of these exploitation films did well at the box-office. But it wasn’t until Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and Sunday Too Far Away (1975) that the revival of the Australian film industry gained the ‘cultural’ stamp of approval.

Both director Sandy Harbutt and executive producer David Hannay, interviewed in Stone Forever, express how disheartened they were about the way the film was treated by the incoming Australian Film Commission (AFC) that was the successor to the Australian Film Development Corporation (AFDC), which had operated from 1970 to 1975. The AFDC had supported a ‘low budget’ production approach geared to the local market and had funded Stone and Barry McKenzie. Hannay and Harbutt were also indignant that Stone was left out of a selection of 32 Australian films for the London Film Festival in 1978. They give grounds as to why they think this happened and also why Sandy Harbutt never directed another film again, although they tried to secure funding on numerous occasions. Hannay felt that the AFC didn’t want to fund the kind of films the AFDC had been making and that the AFC thought that films like Stone and Barry McKenzie were commercial and not ‘nice’ pictures.

Indeed, there were many debates during the early 1970s about art versus commerce in the development of an Australian cinema. The new Australian Film Commission was established, according to the Australian Film Commission Act 1975, 'to develop film as a cultural form of expression, contributing to “national identity”; and to develop an industry …’ The AFC tended to operate 'with an explicit “film as business” / “film as art” dichotomy’, according to Elizabeth Jacka and Susan Dermody in The Screening of Australia Vol. 2 (1988). In those early years most of the films funded by the AFC conformed to what Jacka and Dermody termed 'AFC genre’ films and funded films depicting a picturesque and nostalgic past rather than the not-so-pretty contemporary world.

Kuipers, in an article in Urban Cinefile, uses a quote from Tom O’Regan which seems pertinent here, ‘Stone however, can be regarded as the unacknowledged bastard stepchild of the 70s mode of “high cinema”, banging its oversized and malformed head against the water pipes of cinema’s attic in an effort to be heard’.

In Stone Forever Kuipers interviews many of the actors in 1998 and juxtaposes them with interviews done for the ‘making of’ documentary in 1972 when Stone was being shot. It’s ‘gold’ for a filmmaker to have access to this kind of actual footage from the time of shooting. It’s fascinating to see Sandy Harbutt, David Hannay, Helen Morse, Ken Shorter, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Vincent Gil and Rebecca Gilling and the others interviewed in 1972 and then 26 years later hearing them reflect back on their experiences, telling hilarious stories and making some surprising admissions. Other Australian documentary examples that include this kind of ‘gold’ are First Contact (1983), The Mascot (2004) and Not Quite Hollywood (2008). This often extraordinary footage helps make these films very compelling. Stone Forever focuses on the achievements of the film and the hows and whys of its production rather than taking the opportunity for social analysis of, for example, the depiction of the women characters.

Stone Forever screened with Stone (1974) at the Sydney Film Festival in June 1999. This was the first time Stone (1974) had ever been shown at an official Australian film event. Kuipers describes the night, ‘The audience was a fantastic mix of outlaw bikies, regular bike enthusiasts and festival-type film buffs who wanted to know what all the hoopla was about. Director of the Sydney Film Festival Gayle Lake described it as one of the highlights of the festival. My feelings that night were predictable: pride in having documented a true outlaw film that refused to die after being officially abandoned. More than that, it felt like I’d helped the film and director Sandy Harbutt earn some long overdue approval. For me, the screening night was like a “coming out” party’.

Stone Forever first screened on SBS TV on 11 December 1999.

- Overview

- Curator’s notes

- Video 3 clips

- Principal credits

- Find a copy

- Make a comment

- Map

- Add your review