Patricia Lovell

See also

- 1970s

- 1980s

- actors

- AFTRS

- children's television

- directors

- film industry

- filmmakers

- film production

- television

Related people

- Bruce Beresford

- Ken Cameron

- Melanie Coombs

- John Ewart

- Helen Garner

- Trevor Graham

- Ken G Hall

- Ken Hannam

- Robert Stigwood

- Peter Weir

- David Williamson

Related events

NFSA Historian Graham Shirley looks back over the career of Patricia Lovell, recipient of the 2010 Ken G Hall Film Preservation Award.

Like many first-time Australian feature film producers in the 1970s, Patricia (Pat) Lovell learned about a producer’s role and responsibilities from the films she produced. Guiding her through the filmmaking process were the directors, co-producers and crews she worked with, and above all else, her passion for the subjects she chose. Lovell was also motivated by an appreciation of good storytelling and of quality production values that enabled her films to compare with the best of the others in Australia’s 1970s–'80s feature revival.

Born in Sydney, Lovell was among the six children of Letitia Evelyn nee Forsythe and Harold George Parr. The death of three of her siblings and her parents’s divorce brought painful early years, but she later credited her mother for nurturing her ability to conjure up fantasy worlds and for encouraging her love of reading. Following her parents’s divorce, Patricia moved with her mother to Moree, NSW, and then attended Presbyterian Ladies’ College in Armidale. It was during her school holidays in Sydney that she became an avid filmgoer, admiring especially the masterworks of French cinema including Les Enfants du Paradis (1945, Marcel Carne) – which she saw four times in as many days – and La Belle et le Bête (1946, Jean Cocteau). After leaving school she trained briefly as a librarian and did voluntary work as a stage manager in community theatres. It was while Patricia was working at the Metropolitan Theatre that she met her future husband, actor-producer Nigel Lovell, with whom she had two children. They divorced in 1971.

Joining the Australian Broadcasting Commission in the early 1950s, the then Patricia Parr had a variety of behind-the-scenes jobs before becoming a performer in ABC children’s broadcasting. Of her ABC radio work, she later said she had 'to become an instant actress doing little parts and performing with very well established actors. It was frightening as hell, but it was a tremendous challenge.’ On ABC-TV every Monday afternoon for three years from 1957 she was compere of The Children’s TV Club (1957–61), appearing with Athol Fleming, John Ewart, Gina Curtis and others in a magazine format that included a pantomime, quiz and educational segments featuring the likes of composer Lindley Evans and painter Jeffrey Smart.

From 1960 to 1975 Lovell was widely known as ‘Miss Pat’ in the ABC-TV children’s puppet series Mr Squiggle and Friends (1959–2001). During this time she worked with producer-director-writer Beverly Gledhill, whom she described as 'a woman of energy and crazy enthusiasm’. For a decade from 1964 Lovell also appeared as a panellist on ATN-7’s daytime show, Beauty and the Beast (1964–73). Having been invited to join because the show’s producer and director thought she would fit their need 'for a nice little housewife type’, she often crossed swords with grouchy host Eric Baume. Lovell later recalled that having to confront Baume on air taught her how to stand up for herself. 'By throwing down the gauntlet, Eric forced me to vow time after time, “I’ve really got to get this bastard.” … That legacy of fighting back has remained, thanks to him.’

Lovell’s 1969–75 work as anchorwoman of ATN-7’s early morning Sydney Today show introduced her to many of Australia’s new-generation feature filmmakers, one of whom was Peter Weir, whose short film Homesdale (1971) she particularly admired. Keen to produce a feature adaptation of Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, Lovell invested much of her own time, money, and faith in guiding the project, to be directed by Weir, through its vital early phases of writing and fundraising. Financed by the South Australian Film Corporation, Greater Union Theatres and the Australian Film Development Corporation, Picnic at Hanging Rock became, on its 1975 release, one of the iconic box-office breakthroughs of the industry revival. Its interpretation of the Australian landscape, always a strong ingredient in Lovell-produced films, brought dreamlike foreboding to its tale of lost schoolgirls, touching and haunting audiences for years to come.

Lovell told Susan Mitchell:

If a woman has talent, she’ll get there. But she has to be willing to fight. I could have easily sat back with Picnic and said, 'Okay, you’re the bright organising boys, and Peter’s the talented creative person, so I’m stepping out.’ It probably would have saved me lots of sleepless nights. Naturally, because I’d fought for the thing for so long, I couldn’t do it … I watched and thought, ‘I do know how to organise a film!’ You’ve got to have tremendous determination and be single-minded about it.

At Picnic’s first Sydney screening at the State Theatre, Lovell was approached by veteran producer-director Ken G Hall, who, she later recalled, said 'Congratulations, Pat. Now come on, look pleased. I know it’s your film.’ In the ensuing years, Hall was to become Lovell’s mentor, frequently exchanging notes and ideas with her until his death in 1994.

In her autobiography No Picnic (1995, pp 319-320), Pat wrote:

Through the years I’ve received steady encouragement from Ken G Hall, one of my cinema heroes, sadly no longer with us, whose pioneering film career in Australia is a shining beacon to us all. Who could fail to be inspired to fight on, having received such encouragement as:

'I often think of you and the sterling, and as far as I know, more or less single-handed battle against the titanic odds against you that filmmaking in this country has, more or less, always been. You, my good lady, made a great contribution and I am sure you have more to give, and it is my sincere hope that you get that chance to give further … Warmest regards to a BRAVE LADY. Love, Ken’

KG wrote that note to me when I gave up my office in October 1991 – I certainly can’t let him down!

In 1979 Peter Weir invited Lovell to produce Gallipoli (1981), which had initial difficulty raising funds. When the film’s original backer, the South Australian Film Corporation, withdrew claiming that the project was uncommercial, Lovell bought out their interest. While Weir and writer David Williamson worked to simplify and make the script affordable, Lovell secured the film’s eventual $2.8 million budget from Greater Union, a consortium of businessmen, and – in a coup that made the film possible – a new company, Associated R & R Films, backed by Rupert Murdoch and Robert Stigwood. A major box-office success in Australia, Gallipoli (1981) was the first Australian feature released in the US by an American major, Paramount. The film enhanced the sense of Australian national identity associated with the Gallipoli legend, an influence that lasts to this day. Again the uses of landscape, including its South Australian re-creation of the Gallipoli landing site, were among the production value strengths of this stirring, lyrical film.

Between her two Weir films, Lovell produced two features directed by Ken Hannam, the less commercially successful but atmospherically resonant Break of Day (1976) and Summerfield (1977). In Lovell’s view, the former was too much of 'a slow-moving pastorale’ but Greater Union told her that it did better at the Australian box office than most American films. Despite poor domestic reviews, Summerfield (1977) again attracted good audiences, and its moody exteriors filmed on Churchill Island on Victoria’s Westernport Bay can still send a shiver up the spine.

In contrast to the happy experience of Gallipoli (1981), Monkey Grip (1981) took a personal toll on Lovell. Approached by writer-director Ken Cameron to produce this adaptation of Helen Garner’s popular novel, Lovell postponed the project in 1979 when its budget was impossible to raise due to investor caution over its themes of sensuality and drug-taking. Lovell found funding for the film in 1981 when the 10BA tax concessions were introduced to encourage Australian film and television production. When one of the investors withdrew their $200,000 after the film had started shooting, Lovell was hospitalised for two days with nervous exhaustion. She has credited John Daniell, the Australian Film Commission’s then Director of Project Development, for saving the film by having the AFC match the lost investment. The completed Monkey Grip (1981) was an emotionally honest, caring slice-of-life with stand-out central performances by Noni Hazlehurst, Colin Friels and, in supporting roles, Alice Garner and Christina Amphlett.

Unable to find a distributor, Lovell started distributing Monkey Grip (1981) herself. When the film earned $40,000 in a single Melbourne weekend, Roadshow Distributors took it on. Monkey Grip (1981) has remained among the most dramatically potent and timeless of all Lovell’s productions. Her most recent feature, the telemovie The Perfectionist (1987), was adapted from another strong source, a play by David Williamson, and she has also produced the documentaries Monster or Miracle? Sydney Opera House (1973, Bruce Beresford) and Tosca: A Tale of Love and Torture (2000, Trevor Graham).

Between 1996 and 2003 Lovell was head of Producing at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School, where she used her experience to foster the visions of young creative producers. Rod Bishop, Director of AFTRS between 1996 and 2003, recalls:

In the 30 years I spent in film education, Pat was one of the three most dedicated teachers I had the privilege to work with. Her commitment to her students was in extremis. She held nothing back and gave her all. The students loved her and as with all the greatest teachers, their lives were changed by the experience. Her successful students are too numerous to list here, but I would like to mention those who entered the league of the Academy Awards. Steve Pasvolsky was a builder working on filmmaker Bill Bennett’s house when Bennett encouraged him to apply to AFTRS. Pat took him on and before Steve had finished the course he had written and directed a short film Inja (2001), produced by another of Pat’s students Joe Weatherstone, which was nominated for an Academy Award. Pat’s student Melanie Coombs produced the Academy Award-winning animation Harvie Krumpet (2003) for writer-director Adam Elliot.

In 1978 Pat Lovell was awarded the MBE in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours list for her services to film and television, and in 1980 she received the AM (Member of the Order of Australia) in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list for her services to the film industry. In 2004 she won the Australian Film Institute’s Raymond Longford Award, and she was a commissioner with the Australian Film Commission between 1977 and 1983.

Between 1981 and 1983, while serving as a member of the National Library of Australia’s National Film Archive Advisory Committee, Lovell was a staunch advocate for what the future of such an archive should be. Lovell is the recipient of the NFSA's 2010 Ken G Hall Film Preservation Award for her three decades of involvement in, and advocacy of, the activities of the organisation; especially in her promoting the cause and needs of the organisation to politicians, film industry colleagues and the community at large. Continuing to deposit materials from her films with the NFSA, she has remained a firm believer in the Archive’s value.

External Links

Citations

- This is the ABC: The Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1932-1983 (1983)

Inglis, KS

Publisher: Melbourne University Press, Melbourne - No Picnic: An Autobiography (1995)

Lovell, Patricia

Publisher: Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney - The Long Road to Picnic: The Hazards of Being a Film Producer (2007)

Lovell, Patricia

National Film and Sound Archive Longford Lyell Lecture, 23 October 2007 - Tall Poppies: Successful Australian Women Talk to Susan Mitchell (1984)

Mitchell, Susan

Publisher: Penguin Books, Melbourne - Australian film, 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production (1998)

Pike, Andrew and Ross Cooper

Melbourne: Oxford University Press ISBN 0195507843 - The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry (1990)

Stratton, David

Publisher: Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney - The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival (1980)

Stratton, David

Publisher: Angus & Robertson, Sydney

- Titles

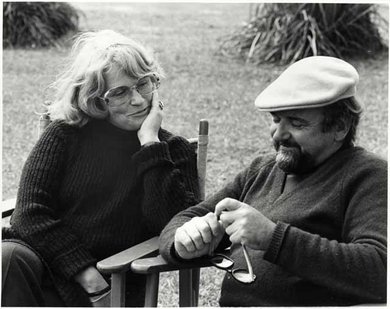

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography