David Elfick

See also

- Australian film

- careers

- directors

- location

- musicals

- newsreels

- producers

- publishing

- surfing

- television

- writers

Related people

- Gillian Armstrong

- Ian Barry

- Bob Ellis

- Albert Falzon

- George Greenough

- Terry Jennings

- Stephen MacLean

- Ian 'Molly' Meldrum

- George Miller

- Philippe Mora

- Richard Neville

- Bojana Novakovic

- Phillip Noyce

- Jeremy Thomas

- Albie Thoms

- Steven Vidler

Related events

Paul Byrnes speaks with David Elfick, the man who helped bring Newsfront and Rabbit-Proof Fence to the screen, about what makes a successful film producer.

The classical definition of a film producer is a person who can spot talent, raise finance, assemble a team starting with a good director and keep them on track through the dark woods of making a film. He or she must be both mother and father to the production.

What they don’t necessarily teach you in film school is that a producer needs to be able to run fast, for when your screenwriter takes off up the road with the only copy of the re-written script, of which he disapproves; you must be cunning, so that when you decide to shoot a controversial story in the place where it happened, you schedule those scenes at the beginning of the shoot, so you’re gone before word leaks out. You must be flexible, so that when your director says he needs another $2 million to make the film really good, you are prepared to go and argue for it. It’s also helpful to have the sensitivity of an artist, the hide of an elephant, and plenty of confidence.

Very few producers in Australia have all of these. David Elfick does, and that may be why he has survived in the Australian scene for 40 years. And not just survived. He has produced some of the most significant Australian films of those years. Anyone who had superintended both Newsfront (1978) and Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002), both directed by Phillip Noyce, could retire happy. Newsfront (1978) has a strong claim to be the greatest film we’ve ever made in Australia and Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002) was a cultural breakthrough – a serious, moving, important film about Indigenous experience that the rest of the country wanted to watch.

Much of the credit for these goes to Phillip Noyce, of course, but Newsfront (1978) was Elfick’s idea. He brought Phillip Noyce, then unknown, onto the project. Noyce returned the favour on Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002). That started with a screenplay written ‘on spec’ by Christine Olsen, after she read Doris Pilkington Garimara’s book. She got it to Noyce to read, and he invited Elfick on as executive producer. Elfick’s career is a stark reminder that film is a collaborative art.

Masterclass

If it is true that Australia lacks enough great screenwriters, it is also true that we do not have enough great producers. In that respect, Elfick’s career is a masterclass. He has survived longer than almost any of his contemporaries, with his optimism intact. He has had some legendary arguments with his collaborators, but most of them still speak to him. More than a few remain close friends.

He is known as ‘Elf’ to many of them, and indeed he is elfin, if it is possible to be a more than six-foot tall elf. At 68, he remains thin, sinewy and athletic. He lives in Bondi, the filmmakers’ ghetto of Sydney, in a house paid for by a successful mini-series. He’s in the surf most days, maintaining a link with the sea that goes back to a childhood in Maroubra, where he grew up in a working-class family, the son of English migrants.

The sea has been good to Elfick. His first films were surf movies, two of the best ever made in this country (Morning of the Earth, 1972; Crystal Voyager, 1973), and he was one of the founders of Tracks in 1970, the irreverent alternative surf magazine that’s still going. With John Witzig and Alby Falzon, he produced it from a rented house in Palm Beach, and that remains the name of Elfick’s company, Palm Beach Pictures.

Elfick has produced 13 features since Newsfront (1978), four mini-series and a mixed bag of documentaries. He has directed four of those features himself. That’s unusual in Australia, where producer-directors are much less common than writer-directors. He would prefer not to produce when he’s directing, but he has never ‘had that luxury’. Elfick:

There are not many people who produce and direct their own material without a lot of backup. I lacked a strong producer, to not only do the worrying about raising the money, which is time-consuming and takes your focus away from being the director, but also the actual endplay of the film, in delivering it. It is much harder when you are the producer-director to hardline the distributors.

Love in Limbo, which he directed in 1993, was a case in point. It had Russell Crowe in an early comedy role. It came out while he was directing No Worries (1993), and the distributors changed the name, against his instincts. He didn’t have time to fight for it.

If you have a strong producer he can make you see what you are doing. With Rabbit-Proof Fence, Jeremy Thomas [the English producer who was selling the film internationally], Phillip and I looked at it and we all agreed that the start did not work and the end did not work. I needed to go out and raise some more money so that we could reshoot. Phillip said 'great’. Now that’s the producer talking to the director, saying we’re not happy with that, let’s reshoot it. No-one’s doing that to me.

It’s about having someone questioning what you are doing, but not feeling threatened by them. When I produce and direct a film, no one is questioning what I’m doing.

Some directors might think that is the perfect set-up, maximum freedom, but Elfick doesn’t agree:

For instance, I think I contributed an enormous amount to Newsfront and Phillip would be the first one to say so. I mean, why I love working with Phillip, it’s really simple. He is so open to ideas, so you can suggest, ‘Why don’t we do this or do that?’, and he often takes the idea and rejects it and tells you why, but he really looks at it, he really gives it the time … What I don’t like are people who say ‘I don’t want to reshoot anything’. I’ve had directors like that who say, ‘It’s fine, don’t worry about that, just look after the money’. I feel like saying, 'You’re a tosser, I’m giving you this great chance to do this movie, and you speak to me like that’. It’s silly.

Discovering drama

Elfick’s childhood was spent in a modest two-bedroom house in Maroubra, with two older brothers. His father worked in a factory, but was well read and self-educated. His mother had trained as a ballet dancer. ‘We moved away when I was about 13 to a southern suburb which was totally miserable for me’, he remembers.

He left school at 16, an unhappy teenager, but decided two years later that he needed to matriculate, so he enrolled in evening classes ‘and just went for it’. He won a Commonwealth scholarship and arrived at the University of New South Wales in 1964, to study drama, English literature and political science. The four years at university were formative. He was a member of the university film club, Opunka, and vice-president of Dramsoc, the drama society.

‘I became very entrepreneurial in the drama society. I was silk-screening posters and putting on lunchtime plays and we hired the AMP theatre down at Circular Quay for a revue.’ He played the lead in Opunka’s first movie, The Hard Word, directed by Michael Robertson. In his final year, he took a job teaching English at a Catholic school in Marrickville, the only long-haired atheist on the staff. A Melbourne friend, Phillip Frazer, recognized his love of music and asked him to set up a Sydney office for a new music magazine aimed at teenagers, called Go-Set.

Elfick began writing stories about the Sydney music scene, covering gigs, liaising with record companies, selling ads, and delivering copies of the magazine to newsagents. Molly Meldrum and Stephen MacLean both worked for Go-Set in Melbourne. Both would later work on Starstruck (1982), written by MacLean, with songs produced by Meldrum.

Elfick found he was good at magazine publishing. The Sydney edition of Go-Set soon outsold its Melbourne parent. The company grew into a small publishing empire, with new titles like Gas, and Revolution, an edgier publication aimed at an older audience. ‘The newsagents hated it because it was obscene and profane. I was also writing stuff for Richard Neville’s Oz in London, so life was interesting, but the deadlines were constant … You didn’t sleep.’ He was so busy that he carried a reel-to-reel tape recorder beside him as he drove the Go-Set van, so he could tape his stories while driving.

In mid-1969, ABC television started a ten-minute Monday-Thursday music program for teenagers, called GTK, which stood for ‘get to know’. The first director was Ric Birch, later famous for doing the opening ceremonies of several Olympics. Elfick became a talent interviewer for the show. He was younger and funkier than the average ABC journalist. Elfick also began to travel, courtesy of an airline sponsorship for Go-Set from Pan American World Airways. ‘I went to London and interviewed Pete Townsend from The Who, went to his house, met Thunderclap Newman, lots of terrific people, two weeks in London and then I would have to fly back and do the next issue of Go-Set.’

GTK (1969–74) became a kind of film school for Elfick. He was involved in directing and editing a series of short films for broadcast on the show. He was also part of the underground film scene, based in the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative and the experimental group, Ubu Films. ‘It was a very interesting and creative time in Sydney.’

Making Tracks

He didn’t know, but he was acquiring the skills he would need to become a producer: confidence, entrepreneurial drive and an ability to read the marketplace. He learned on Go-Set that magazines needed ‘a captive audience’. Surfers were an emerging audience, but there were only two glossy surf mags in Australia. Elfick felt both were badly written and out of touch. They also took four months to reach the newsstand, because they were printed in Singapore or Hong Kong. He decided to challenge them, by printing on newspaper stock, being more topical and cheeky and plugging into the ‘alternative’ culture then emerging around surfing. He also poached the editors of both glossy magazines, John Witzig and Alby Falzon, to join him, hoping that that would help him steal a march on the rivals.

They called it Tracks, and it was an instant hit with young people, male and female. ‘The main thing I took from Go-Set was that you have to let the kids write in and dictate the policy. And of course, we went for humour with Tracks. We got lots of girls writing in, with the funniest letters. The letters to the editor page in Tracks became a must read … It was kinda great fun, and it just worked from day one. It’s still going, all these years later.’

Alby Falzon had been shooting material for Bob Evans’s surf films since about 1964. He wanted to make a new film, in a different style. Elfick had taken the Pan Am sponsorship with him when he left Go-Set. He had helped with the soundtrack for Paul Witzig’s groundbreaking 1969 surf film, Evolution. ‘I said to Alby Falzon, why don’t we do it together and why don’t we use my airfares, and my contacts in the music industry to create a really innovative soundtrack? He had already shot a lot of stuff around New South Wales, and there was this fledgling industry body, the Australian Film Development Corporation (AFDC), so we applied and got some money to do the soundtrack actually, not the film, and to buy some 16mm film projectors.’

Pan Am flew them to Jakarta. They went overland from there to Bali: two filmmakers and two surfers – former US champion Rusty Miller, a longboard specialist, and ‘a 14-year-old hotshot grommet’ called Steven Cooney, from Narrabeen, NSW. Falzon went out on a motorbike and discovered a promising break near the airport. Elfick:

The first wave ever ridden at Uluwatu is in Morning of the Earth (1972). We took the title from what the Indian Prime Minister Nehru said when he arrived in Bali, ‘This is the morning of the world’. So we had, ‘One ocean once covered the world, it was the Morning of the Earth, a fantasy in three unspoiled lands’, which were Australia, Bali and Hawaii. There are no cars or high-rise buildings in it, it’s like a fantasy or an opera, in the way the narrative is told by the songs. The themes of the film are reinforced by the songs. I got Albie Thoms, who was an underground filmmaker, to come and work with Alby Falzon on the editing, so the film would not be like a traditional surf movie, more like an alternative movie, but around surfing.

And with Tracks, we had the opportunity to really promote that film well. And we had the two Eiki projectors, from the AFDC. I would take a projector up the coast, with my girlfriend, in a panel van, and set it up in places like the Coffs Harbour Civic Centre, and collect the money and put the handbills out. The film made its money back after two weeks. We went in with the cash and gave it back to the AFDC, two guys walking in with $25,000 in cash!

The film took more than $200,000, making it the most successful Australian surfing film to that time. The profits financed the making of Crystal Voyager (1973), an innovative idea, because it was the first surfing biopic. It started as a short film about George Greenough, a Californian fisherman, surfer, inventor and cameraman, whose radical ideas about board design had a huge impact on surfing.

Morning of the Earth was Alby Falzon’s vision, no doubt about that. George Greenough was the most interesting guy in surfing, the perfect subject for our next step in moviemaking. He was the first guy to build a camera to shoot inside the curl of a wave. I was in America and George was living in Santa Barbara at this time and building his own boat with his design for a retractable keel, so that he could sail around the world to find uncrowded surf…

George knew us because he was a surfer and when you came to Sydney, you ended up sleeping on the Tracks floor if you had nowhere else to sleep. George had made a movie called The Innermost Limits Of Pure Fun (1969), which was a very interesting experimental sort of film. He is an eccentric guy. He and I hit it off. So we rented a farmhouse near Santa Barbara and Alby came over and we started to film. We went on various surf trips, and decided to make it into a feature.

Falzon read that a new cinema was being built into the redesigned Sydney Opera House. ‘He said we should get it. It was his idea.’ Elfick booked the cinema for its first three months. That sounds like an enormous risk, but he was already involved in film exhibition. He had leased the Manly Silver Screen cinema with surf filmmakers Paul Witzig and Peter Troy. They were programming surf movies and alternate films to young audiences, in much the same way that Tracks was a newspaper for that age group.

Elfick and Greenough agreed that Pink Floyd’s 23-minute track 'Echoes’ would make a great accompaniment to Greenough’s footage from inside the wave, to end the film. Pink Floyd had the number one record in the world, Dark Side of the Moon (1973). Elfick flew to London, hired a cinema, showed them some of Greenough’s footage and persuaded them to let him use 'Echoes’, with no money up-front. Instead, he offered them free use of the Greenough footage, which they used onstage on their next American tour.

Crystal Voyager (1973) premiered in the Sydney Opera House cinema in a 16mm version that Elfick did not think was ready. Elfick and Falzon parted company, and split their joint assets. Elfick and Greenough re-edited Crystal Voyager, with Greenough providing a voice-over narration. They blew it up to 35mm for international re-release. It became a smash hit in the UK, running for six months in the West End.

Elfick was now ready to make a feature film. He wanted to get away from surfing. He seized the opportunity to go on the set of Mad Dog Morgan (1976) and do a ‘making of…’ documentary, To Shoot A Mad Dog. He had met the producer Jeremy Thomas and director Philippe Mora in London and was impressed with their two compilation documentaries, Swastika (1974), and Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? (1975). Elfick decided to make a feature film based on Australian newsreels.

Behind the news

The origins of this idea are mired in controversy. Elfick discussed it originally with many friends – including Richard Neville, Philippe Mora and Andrew Fisher, an Australian lawyer based in London who worked with Neville on the legal defence of Oz magazine. ‘Initially, we were going to do a documentary using newsreel cameramen. And it was going to be the story of two brothers. Andrew and I applied to the AFC (Australian Film Commission) for some money. This was before Bob Ellis or Phillip Noyce were involved.’

The idea evolved when Elfick realised that you could blend the story of two fictionalised brothers into the newsreel footage:

I thought, there’s this exciting old footage. Why don’t we just write a story where we put our characters into the exciting footage, and tell a story of the changing face of Australia and the beginning of television? As a child, we used to sit around the radio at home every Sunday night and listen to the radio play, and then one Sunday it stopped, because television had started in Australia. We all used to listen to the serials, you know, Hop Harrigan (1942–48) and all those things, and suddenly we were watching The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–59) instead of listening to Australian-made serials on the radio.

Elfick had been impressed by a musical play co-written by Bob Ellis and Michael Boddy, The Legend of King O’Malley (1970), so he asked Ellis to write a script:

Bob wrote a draft of the screenplay, and it was good, but it was very long. I have various versions of it here and some of them are 200 foolscap pages. I got Phillip on as the director. Newsfront took a long time to develop. Roadshow became involved through Greg Coote, who was enormously supportive. It helped that Crystal Voyager (1973) had been released in 35mm. Roadshow were very good, incredibly supportive. Greg said 'I want you to be involved in the marketing, but I can never find you’. There were no mobile phones or anything, so he said ‘I will give you an office in Market Street for three months, so that when we are making decisions, you are here’.

Elfick and Noyce developed a strong friendship:

There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing on the script. It was too long. While we were wildly ambitious about it, we realised that it needed cutting. Bob is a wonderful writer but he needed an editor. So we just had to get in there and be a bit brutal, because we had to fit it into a six-week shoot and we had $500,000.

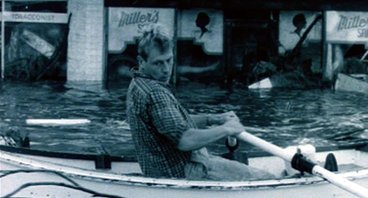

I said to Phillip we have got to put all our money into one big set piece that makes us believe, that puts our actors back into real events. And that’s got to be the Maitland floods, because that is where Chris [the junior cameraman, played by Chris Haywood] drowns. So I said, 'Let’s try and reconstruct the main street of Maitland. And let’s have them go down the main street of Maitland in a flood, and then we can cut to the real footage, which is fantastic, and then people will believe. That’s the lie in the movie that makes it the truth, you know?’ Phillip agreed with that, so we built the main street of Maitland, an incredible set, in Narrabeen Lake. We cut lots of Bob’s script, and Phillip rewrote stuff.

I lived on the hill in Palm Beach on Sunrise Road, and Bob was so late with the script. I got him to come to my place once, this is true, and I locked him in the back room, and I said I am going for a surf, and there better be a few pages come under that door when I get back, because I’m not unlocking it until they do. He escaped and I got no pages, but soon after that he bought the house next door.

Phillip and I were working down at the Palm Beach Studios [a converted dance hall that Elfick now co-owns], finishing the script. I thought Phillip had done a good job. Bob came down, he read it in our presence, and he then just exploded. He ran off up the hill with it, and it was the only copy we had. There is a story that I crash-tackled him on the road but it wasn’t like that, it wasn’t hard to catch Bob. I just grabbed him and grabbed the pages back off him.

Then Bob just went feral. I’ve still got all the documents in the files. He sent me a telegram saying we were officially dismissed from the movie, and Howard Rubie was taking over directing it, and then actors would ring us up and say Bob has cast me in the lead. And I would have to say, well actually, he’s not doing it. I had to ban Bob from the movie set. I just said, 'We’re going to shoot the movie and you’ve got nothing to do with it’.

Ellis was never fired and he was paid for his script, but the schism was irredeemable.

Why Phillip and I succeeded is that, he’s six foot six [198 cm] and he’s very confident and at that stage I was very confident too, and we would go into these funding bodies, who didn’t want to give us the money, and it was the ‘But What if He’s Right?’ theory. We were almost scary in our enthusiasm and our size and our energy and confidence. Phillip and I, you could never get between us, because we were loyal to each other, and it’s a very interesting thing that we made a film about loyalty. We realised that the minute I doubted Phillip, or he doubted me, we were gone. It would have fallen apart.

When the film was finished, they invited Ellis to a screening with the main investors. At the end, Ellis declared it the worst film he had ever seen, and told them to take his name off the credits. Elfick negotiated a compromise through Jane Cameron, Ellis’s agent, to keep his name on the end roll-up.

The film was a major box-office success, and it won the major AFI awards in 1978, against tough competition, including best film, director and screenplay (awarded to Ellis). The enmity between Ellis and the other two principals lasted for 20 years, until an anniversary screening at the Sydney Film Festival in 1998, coordinated by Frans Vandenburg, the assistant editor on the film. All of the main creative participants took part in a panel discussion, including Ellis. He conceded at that session that Newsfront was indeed a considerable achievement. A rapprochement of sorts took place.

Into the ’80s

Elfick’s next production was a thriller called The Chain Reaction (1980), written and directed by Ian Barry. The film went considerably over budget, and became ‘a bit of a nightmare’, says Elfick. George Miller, who had recently made his debut with Mad Max (1979), came in to help direct the action sequences and Elfick helped with the second unit. The Australian box office was disappointing, but the film sold to Warner Brothers for the rest of the world and did well in some territories, including Japan.

Elfick had now been around filmmaking for more than ten years, without ever having made a decision about what kind of career he wanted:

I did not think that I was going to become a successful producer but that’s where I was, so that’s what I was doing. Having learned filmmaking as filmmaking, fiddling around in editing rooms with surfing movies, directing the little things at GTK, suddenly I was the producer. I enjoyed doing the second unit on The Chain Reaction (1980). I did a little second unit on Newsfront (1978) too.

I realised I couldn’t have directed Newsfront, nor the drama of The Chain Reaction, I didn’t know enough as a director to do that and I hadn’t yet formed my own views, but I could get films made, and every film I got made had a high profile. Every film was a bit of an event, and all of them had done okay. None had lasted a week and disappeared.

During a trip to London, he caught up with his old friend Stephen MacLean, who had been a writer on Go-Set, and then a director on GTK. They talked about MacLean’s colourful childhood in Melbourne and MacLean’s desire to write a script about growing up in a pub. Elfick gave him £300 in travellers cheques, all that he had, and told him to get to work. That film became Starstruck (1982), and the script attracted a high-profile young director.

Gillian Armstrong had made her debut two years earlier with My Brilliant Career (1979). Starstruck offered a change of pace and style, a musical comedy with a high-camp style, primary colours and Sydney Harbour views. Elfick says it was a difficult film to produce, because nobody had done a musical in Australia before. Richard Brennan, who worked on Newsfront (1978), joined forces with Elfick again to produce Starstruck. Elfick and MacLean felt they had good instincts for selecting the right pop music for the young target audience, because of their experience on Go-Set:

When you worked on a colour magazine like Go-Set, it takes a month to do the colour separations for the centrespread or the cover, so if you can pick what will be the hottest songs in Sydney in a month’s time, then you’re going to sell more papers; and if you can have them as a double-page spread in the middle as well, every kid’s gonna want it, especially if that song has gone to number one.

Elfick and MacLean knew many good songwriters, who offered new songs, but Gillian Armstrong had different ideas about the music. After much discussion, Elfick deferred to her. ‘Gillian had her views on the music and she was the director of the film … The soundtrack is pretty good on Starstruck. Molly Meldrum did a great job producing many of the songs. He’s a great producer, with a great ear.’

The film did respectable business in Australia. Armstrong supervised a re-cut and shortened version for the US release. ‘The American release is much better than the Australian version’, says Elfick. ‘I think one of the problems was that its actual appeal was to a certain group of girls of a certain age, and it didn’t appeal to older kids or younger kids.’

Elfick produced three more movies in the next five years, each in a different style, with a different writer and director. Miranda Downes wrote Undercover (1983), the story of Fred Burley, inventor of the Berlei bra. The movie was set in in the 1920s and directed in frothy comic style by David Stevens (The Clinic, 1982). Dennis Quaid was to star but he was not well known, so the job went to Michael Paré.

Both Starstruck (1982) and Undercover (1983) were ahead of their time, in one sense. During the ’90s, quirky Australian comedies became much more popular with audiences, but both of these films took early steps in the direction later followed by Strictly Ballroom (1992) and Muriel’s Wedding (1994).

Emoh Ruo (1985), written by Paul Leadon and David Poltorak and directed by Denny Lawrence, was another domestic comedy, but neither it nor Elfick’s next film, Around the World in 80 Ways (1986), directed by Stephen MacLean, found much connection with audiences.

Producer to director

Elfick shifted his focus to television, where the mini-series format was proving very popular with Australian audiences. Fields of Fire (1987), based on a book by an English writer, was about migrant families in the cane fields of North Queensland around the Second World War. Miranda Downes wrote the first series, which was directed by a young film school graduate, Robert Marchand. Downes went to Cairns for a holiday before shooting began, and was murdered on a beach, a crime that had a profound effect on the production. Elfick decided not to shoot the series in North Queensland, partly because the crime was unsolved and he feared for the safety of his actors and crew. Fields of Fire (1987) was made in northern New South Wales, and it was a huge success with audiences, leading to two more series. Elfick began directing on the second series, in 1988.

He followed that with three films on which he was both producer and director – Harbour Beat (1990), a thriller set in Sydney, Love in Limbo (1993), a comedy starring Russell Crowe, and No Worries (1994), one of Elfick’s favourites among his own work.

No Worries was a play for young audiences by a well-established British playwright, David Holman. Michael Bridges, production designer on one of the Fields of Fire mini-series, suggested to Elfick that it would make a good feature film. The story is about an outback family, forced by drought to relocate to the city. The daughter is so traumatised that she stops speaking.

Elfick set the film up as a British-Australian co-production. The English actress Geraldine James joined a fine Australian cast, headed by Susan Lyons, John Hargreaves, and newcomer Amy Terelinck as the girl, Matilda. Holman had written the play as writer-in-residence at the South Australian Theatre Company. Elfick brought him back to Australia to write the script. They toured western New South Wales, looking at locations and discussing the project with local people. Holman decided to keep the story, but completely rewrite the text. He felt that a play was a play, and a film was a film, requiring a different sort of writing. Elfick:

He wrote a film about people being dispossessed by the drought, but the subtext of his whole story was that that family moves from Australia’s white Anglo-Saxon rural past into Australia’s multicultural, urban present.

It was a hard film to make, with dust storms and little kids … But David Holman was there throughout the production and that helped a great deal… I’m very proud of that film.

No Worries (1994) screened in the Kinder filmfest, as part of the Berlin Film Festival, where it won a major prize, the inaugural Crystal Bear. ‘I was so pleased that after it won the prize in Germany, I got a letter from the prime minister, Paul Keating. I was very proud of that.’ The film won a number of other prizes and sold very well for television around the world.

Blackrock (1996) was a similarly difficult project. Nick Enright had written a play inspired by real events in Newcastle: the rape and murder of a schoolgirl on a beach. Enright adapted the play in collaboration with actor Steve Vidler, who was keen to make his directing debut. He had appeared in two films that Elfick had directed. Vidler asked Elfick to produce the film, and he agreed. The production had to avoid any reference to the actual murder, because there were matters in court. Passions were running high in Newcastle, where the filmmakers were accused of feeding off a local tragedy. Elfick scheduled the Newcastle location scenes at the beginning, to minimise the risk. The production kept a low profile, avoiding publicity, but he hired as many Newcastle actors and crew as possible. Because the film has a surfing background, Vidler entrusted Elfick to do the second unit surfing scenes. Blackrock (1996) featured a then unknown Heath Ledger in his first movie role.

Elfick was worried about the emotional trauma of the rape and murder scene for the actors. The victim was played by 16-year-old Bojana Novakovic, who went on to graduate from NIDA, the National Institute of Dramatic Arts. The scene was filmed at night on a beach. Elfick arranged for the actress to be able to speak to her mother on the telephone, in private, between takes.

Following the Rabbit-Proof Fence

Elfick’s next big project was Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002), a production that proved as epic as its theme. Elfick’s involvement began at Palm Beach Studios, the old dance hall he calls his ‘spiritual home’, where much of his film work has been done, as far back as Newsfront (1978). Elfick:

Phillip [Noyce] came to stay at Christmas, and he was going to do The Sum of All Fears (a big-budget film in Hollywood). He said, 'I want you to read this script, it’s pretty good’. I read Rabbit-Proof Fence, and it was a terrific script, you know, I thought, ‘At last a great Aboriginal script, the girls get home to their mother at the end, it’s got an up ending, and yet it’s got really serious subject matter’. But I said, 'You’ll never do it, you’re going back to hook up with Harrison Ford in New York to talk about doing the sequel to something you have done two episodes of already, an incredibly successful franchise. That will take you a year.’ ... But his line producer in America, Kathleen MacLachlan, told him he had to do this, and then Harrison didn’t want to do The Sum of All Fears, so Phillip pulled out too. And he wanted to come back here, and he saw the value in the script.

Noyce said he wanted to produce it, with Christine Olsen as co-producer. ‘He asked me to raise the money and I said okay, I’ll do that for you. I ended up getting an executive producer credit on it.’

Elfick took the project to his old friend Jeremy Thomas, a prominent English producer, who had both a production company and a sales company in London. Thomas agreed to sell the film internationally. Both the casting of the film and the shooting were fraught. The three young Aboriginal girls had never acted before. After a week of shooting, Noyce told Elfick that he wasn’t getting the scenes he needed. There were too many interruptions between takes, and the girls had difficulty maintaining their concentration. Noyce decided to try a different shooting style, putting a larger film magazine on the camera, going handheld, minimising the interruptions to intensify his communications with the girls.

The normal shooting ratio for a feature film is about 12 to 1 – they shoot 12 times more than they use in the final edit – but Elfick had already allowed a shooting ratio of 20 to 1. ‘So I asked Phillip what he thought it was going to be, and he said 50 to 1’.

Elfick told him to go ahead, even though it would add $200,000 to the budget. He took that money out of the music budget. He did not go on set much during the production, but he and Noyce had a long talk every Sunday about every aspect of the film:

He said, 'I’m really worried that the film doesn’t have a sense of journey, and I don’t think we’ve got a good start’. So we finished the film, and it had a budget of $8 million, and Jeremy came out to Australia and we looked at a cut of the film, and it didn’t work. It didn’t work for a number of reasons. The start needed a greater sense of place, the journey lacked a sense of isolation and vast distance, and the end wasn’t as emotionally strong as the screenplay. So Phillip, Jeremy and I discussed it, and the only way to make it work was to do two big pick-up shoots. We re-shot the end up in the Kuring-gai National Park. All the trees and plants are different but no one notices, and of course, the girls were then much more confident, they had done a whole movie, so it was a very emotional ending, and it worked.

The second major re-shoot was in the desert in WA, using a helicopter. We had stand-ins for the girls and we did wider panoramic shots, and we added the rabbit-proof fence digitally. To pay for it, I went to the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) and told them they had to put more money in. Terry Jennings at the FFC was a filmmaker and he understood. I said, 'You’ve got a lot of money in this film and no Indigenous film has worked … this film could work, but not in its present form, and you have just got to put more money into it’, and he said, 'Okay, I’ll push it at the board meeting’.

Then I went to our other big investor, which was Showtime, and I said, 'The FFC are willing to put in more money but they will want it out first’, which means that the first returns go to them, and Showtime went ballistic and said, 'No, no, no, you can’t do that. We don’t want the FFC’s money coming out before us, why should they, they’re a government organisation.’ Showtime had put up some decent money. It was really acrimonious between the two agencies, they really disliked each other. I thought this is crazy, so I said to Showtime, 'Why don’t you put up the same amount of money, and then you’ll get it out at the same time’. They agreed. So the $200,000 became $500,000. But they said, 'Don’t you come back to us again asking for any more money’.

In fact, he did go back and ask for more money, twice. Elfick raised an extra $2 million via this process, part of which allowed Noyce to commission Peter Gabriel’s brilliant soundtrack.

A different ball game

That story is interesting. Conventional wisdom says that a producer who goes $2 million over budget is not a good producer. The risks on this project were enormous, given that no film on an Aboriginal story had been a hit. Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002) became the first, taking $7.5 million at the Australian box office. It is one of the rare Australian films that went into profit, repaying the gamble that the FFC and Showtime took with it. That’s perhaps the final lesson we can take from David Elfick’s career. A great producer must know when to back his director to the hilt, especially when the stakes are at their highest. Like the gambler in the song, ‘Know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em’.

Elfick says that producing films in Australia has never been easy. There were no models for how to do it when he started. ‘It’s a totally different ball game now, but it wasn’t easy then. I tell young people today that it is an exciting and challenging career, and if you are game for it, then you should just go for it.’

External Links

- Titles

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography