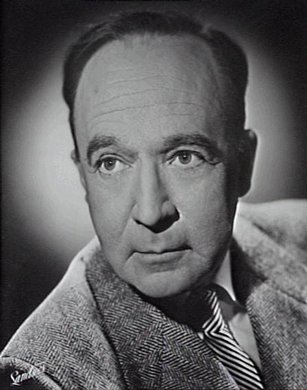

Charles Chauvel

7 October 1897 – 11 November 1959

See also

Related people

- Kenneth Brampton

- Elsa Chauvel

- Errol Flynn

- Ken G Hall

- Ngarla Kunoth

- Raymond Longford

- Chips Rafferty

- Grant Taylor

- Robert Tudawali

- George Wallace

Related events

Charles Chauvel was the most overtly nationalist of Australia’s early directors, and the most independent. Feature films curator Paul Byrnes pays tribute on the 50th anniversary of his death.

In the first 50 years of Australian cinema there were three major directors: Raymond Longford was the romantic, Ken G Hall the populist and Charles Chauvel the nationalist. Longford dominated the silent era, Hall the early sound era of the 1930s, and Chauvel the ‘40s and ‘50s. Longford was perhaps the most gifted, Hall the most successful and Chauvel the most audacious. Each of them changed the way we saw ourselves as a nation, but of these three, Chauvel was possibly the most influential, partly because he saw his filmmaking as part of a national project. He was a committed nationalist, a booster for Australia’s interests. As early as The Moth of Moonbi, his first film in 1926, he saw his films both as entertainment and advertising for ‘our great Commonwealth’.

His love of country both enriched and undermined his achievements. It gave him a desire to tell flattering stories of pioneers conquering virgin territory, as in Sons of Matthew (1949), but it could also lead him into tiresome lectures like Heritage, his 1935 potted history of Australia, in which drama loses out to pageantry and preaching. His greatest films are those he made during and after the Second World War, when he was virtually the last man standing in the Australian film industry. If he had only made Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940) and Jedda (1955), his place in the Australian pantheon would be assured, but Sons of Matthew (1949) and The Rats of Tobruk (1944) were also major achievements. No other Australian director had a directing career that spanned four decades, from the silent era, through the early talkies, the war years and on into the new medium of television. His last project was a series of half-hour films called Australian Walkabout (1958), made for the BBC, in partnership with ABC Television, completed shortly before he died in 1959.

Continuing debate

Fifty years after his death, debate still simmers about the quality and meaning of his films. He is sometimes dismissed as a B-grade action director who was ham-fisted with actors. His early films are certainly crude in performance, but Chauvel was the first to discover some major talents, notably Errol Flynn – and his later films are much more dramatically convincing. More significantly, he never stopped growing as a filmmaker and an artist. His love of country is much more nuanced and complex in Jedda (1955), the first fully-Australian narrative feature in colour, and the first film to take seriously the emotional lives of Aboriginal people. If we compare Jedda to Uncivilised (1936), made two decades earlier, we see how far Chauvel’s filmmaking had come and how much his thinking had changed.

His films before the war are part of an imperial mindset – Australia as outpost of British civilisation, with a duty to tame the land and its original inhabitants. During and after the war, Chauvel’s nationalism and self-confidence grew, along with his technique. The later films assert that independence – tentatively at first, in Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), then with an almost religious fervour (Sons of Matthew, 1949). By the time of Jedda (1955), Chauvel has turned his back on the past, which was the spur for all his earlier films. Jedda looks toward the future and the ‘problem’ of black assimilation. The extraordinary thing about Jedda is that it sees that there is a problem in black and white relations in Australia. Few films before Jedda even admitted this (Bitter Springs, 1950, was one exception). On a deeper level, Jedda is an expression of Chauvel’s great love of his country, without reference to a colonial past and with a kind of longing at its heart. Chauvel had moved from a dream of subjugating the land to a dream of succumbing to its embrace, as the two Aboriginal characters do at the end of the film. That’s a long way from where he started.

Between sword and plough

Chauvel’s family is descended from French Huguenots, who came to Australia via England and India, where they served in the British Army. Charles was born on 7 October 1897 in Warwick, Queensland. His mother Isabella Barnes came from near Casino in northern NSW. His father, Major Allen Chauvel, farmed on the Canning Downs South sheep station on the Darling Downs, owned by Charles’s grandparents. When he was two, Charles’s family moved to ‘Summerlands’, a dairy property in the Fassifern Valley, about 70 kms north-east. Charles Chauvel was thus raised between sword and plough, with strong ties to England, the army and the land. When his father went to the First World War, Charles was left to run the family property, aged 17. His uncle, General Sir Henry (Harry) Chauvel, commanded the Desert Mounted Corps in Palestine. In 1917, his troops mounted the famous cavalry charge at Beersheba, the subject of Forty Thousand Horsemen.

After the war, Charles had been expected to stay on the land, but he went to Sydney instead, to study art, to the great dismay of his father. In Sydney, he attended classes with the well-known artist, Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo, who would also briefly tutor Ken G Hall. He also enrolled in drama classes and took boxing lessons at Snowy Baker’s gymnasium. Baker was a sporting celebrity and showman, who began appearing in movies around 1918. He used horses in all his films and Charles Chauvel’s first job in film was to tend Baker’s horses. He also had a small part in The Jackeroo of Coolabong (1920) and took odd jobs in productions by Franklyn Barrett and Kenneth Brampton. Baker left Australia in August 1920 to break into American films; Charles Chauvel followed him in April 1922. He sustained himself in Hollywood with small parts in movies and by writing stories about Australia for a Hollywood magazine. He worked at MGM, Hal Roach Studios, and on the road with Snowy Baker’s travelling show – he held a cigarette in his mouth that Baker would knock out with a stockwhip. He also did publicity work for Douglas Fairbanks Snr during the shooting of The Thief of Baghdad (1924). Chauvel spent about 18 months in the US, learning everything he could about movie-making. He returned in late 1923, determined to make his own films, with Australian settings.

His first two films were Australian westerns, financed by his friends and family in Queensland. The Moth of Moonbi and Greenhide were both released in 1926, with limited success. Despite his admiration for the American film industry’s production methods, Chauvel found that exhibition in Australia was basically a closed door, controlled by one Australian company and American studio interests who had no interest in Australian production. The protests about the monopolistic behaviour of exhibitors and distributors led to a Royal Commission in 1927 at which Chauvel gave evidence. He was a less confrontational witness than Raymond Longford, but he floated an idea that few others had envisaged – direct government subsidies to filmmakers. This was to become an important part of Chauvel’s working model throughout his later career. He often sought and received direct government support for his projects, based on persuasive arguments to politicians about projects of national interest. Chauvel had learned the value of publicity while in Hollywood, and he worked hard on self-promotion throughout his career. Becoming famous gave him entrée; entrée led to men in power and, sometimes, the money to make a project work. Chauvel never found it easy to get a project off the ground, but he succeeded more often, and for longer than any of his contemporaries in independent production. (Ken Hall at Cinesound was in no way independent).

Partnership with Elsa

Chauvel met Elsie May Wilcox while he was casting Greenhide (1926). She was an actress, working as Elsie Sylvaney. Although born in Melbourne, she had spent much of her childhood in the family theatrical troupe, working in South Africa. She returned to Australia in 1924 and met Chauvel in Brisbane soon after. They were married in 1927 in Sydney and the young couple returned to Hollywood in 1928. For the rest of their lives together, Elsa (as she now called herself) was Charles’s partner in all aspects of his work. She collaborated on research and scripts, and took roles as needed in the films. She was a production assistant on Heritage (1935), assistant director on Uncivilised (1936) and credited co-writer on every film after that. In his book Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel (1991), Stuart Cunningham says: ‘Certainly the partnership was unique in Australia film history, and it enabled Charles to avoid the individualist and masculinist excesses epitomised by filmmakers of the time such as Frank Hurley. Some of the complexity and resonance of Chauvel’s films undoubtedly stems from this partnership… Nonetheless I do not consider that Charles and Elsa’s partnership provides sufficient case for dual authorship. Elsa says as much in her memoirs… Charles’s credits, as producer, director and scriptwriter, show him to have been the main voice in an industry partnership, but the spirit of particularly the later films suggests much more than merely a working relationship’. It might also be said that Chauvel’s early films might have had better acting if Elsa had been more involved in the direction, because she was a highly experienced performer before they even met.

The Chauvels spent a year in Hollywood, trying unsuccessfully to find an American distributor for his first two films. The timing was against them – the films were silent, and sound-on-film was the new thing in movies. They returned to Queensland and settled in Stanthorpe, at an impossibly difficult time for an independent filmmaker. The Depression hit Australia harder than most countries. Making films with sound required expensive new equipment and the Chauvels had a new baby daughter, Susanne, born in 1930. Chauvel did not make another film until 1933, seven years after the two early silents, although he developed several projects.

Chauvel’s films of the 1930s show that he had a foot in the silent era, and a heart swollen with national pride. Much of his instinct for scenario writing was based in silent melodrama, with its penchant for coincidence and revelation. Hollywood in the early 1930s had already moved away from those devices, because it could. It had access to plays and playwrights who wrote dialogue; Australian films had no such access. Scriptwriting was the greatest weakness even at Cinesound, where Ken G Hall had money to pay for it. The Chauvels attempted to find a point of difference in their films, rather than try to copy Hollywood. Charles Chauvel saw this as the only hope, because he thought Australian cinema could never compete with classical American films in terms of resources.

Affinity for landscape

Chauvel looked for a natural point of difference and he found it in the Australian landscape. He had access to backgrounds that other countries could not match, and his films of the 1930s (In the Wake of the Bounty, 1933, Heritage, 1935, and Uncivilised, 1936) are all attempts to maximise the dramatic impact of landscape. He was attracted to place as much as to character. His films of this period are less psychological than topographical. Wake shows no great desire to enter the psychological world of Fletcher Christian, played by Errol Flynn in his first major role (just as well, since Flynn would have struggled at this point to portray anything as an actor). Chauvel would reject this approach to some extent in his later films (he was said to feel embarrassed about the shortcomings of Uncivilised), but he never entirely abandoned it. Jedda (1955) is both a landscape picture and a psychological study of human behaviour. The difference was that the films made from 1940 on are both, rather then relying simply on locations as their major source of drama. What Chauvel never abandoned was his search for epic tone. His films were always BIG, even when they also attempted to become ‘domestic’, as in Sons of Matthew (1949), which is the story of a family. Epic locations required epic emotions, in his style.

It follows that there is very little natural comedy in the earlier films. There is a strong change in Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), perhaps because Chauvel had discovered Chips Rafferty, a young actor who was a natural comedian. Comedy was an essential difference between Chauvel and Ken Hall. Cinesound’s films of the 1930s are governed by a commercial imperative, in which revenue and laughter are entwined, perhaps because of the Great Depression. Chauvel’s films of the 1930s substitute action and location for their entertainment value, a difficult and expensive path to take when you have limited resources. In the Wake of the Bounty (1933) made money; Heritage (1935) lost it, partly because it cost four times as much. Uncivilised (1936) became a make-or-break project that would encapsulate Chauvel’s great dilemma – independence or alignment, America or Australia. It was made for less money than Heritage (1935) but was a deliberate attempt to break into the American market, hence the ‘Tarzan’ storyline. The Chauvels went to the US in November 1936 to sell it, and to broker an agreement between Expeditionary Films, the company financing his Australian films, and Universal Studios. Universal’s Australian head, Herc McIntyre, believed strongly in Chauvel’s potential and the studio offered Charles the possibility of a formal agreement to co-produce and distribute his feature films, something no other Australian producer had been able to achieve. The agreement never came.

Powerful friends

The Chauvels moved to Sydney in 1931, and Charles quickly made powerful friends. He was a key influence, with Frank Thring, in the NSW government’s decision in 1935 to impose quotas on distribution and exhibition companies in order to finance Australian productions. The Deputy Premier of NSW (Michael Bruxner) was an investor in Expeditionary Films. Chauvel formed friendships with politicians in both NSW and Queensland, and promoted himself and his films with great energy – and occasional controversy (see In the Wake of the Bounty, 1933, for a description of his censorship problems). The friendship with Herc McIntyre, head of Universal Studios in Australia, brought him close to forging the much dreamed-of international alliance with a major studio. The Chauvels spent seven months in 1936-37 in Hollywood, with full access to all departments at Universal. When the Australian directors of Expeditionary Films failed to back this proposed alliance, Chauvel resigned in mid-1938 and walked away from the company he had founded. It was a bitter decision, but in his typically resilent way, Chauvel returned with renewed hopes of forming a different alliance – this time with Fox Films Australia.

American distributors operating in NSW now needed Australian films, in order to comply with quota provisions. Chauvel had already aligned himself with the owners of a new studio at Pagewood in Sydney. Much of Uncivilised (1936) was shot at National Studios, and he had high hopes of it becoming a viable rival to Cinesound, the only continuous studio in the country. In the meantime, the NSW quota system was falling apart, with the foreign-backed distributors threatening to withhold all films from NSW if forced to comply. Chauvel had been working on the idea for Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940) since about 1930. With the end of quotas, the NSW government agreed to underwrite the production of new Australian films, one of which was Horsemen. The coming of war in Europe in 1939 may have helped it to get made, because it was considered a patriotic project.

Success in wartime

When all other feature production in Australian was coming to a standstill, Chauvel was able to keep working. Indeed, he had his greatest success in the war years, making a second feature, The Rats of Tobruk, in 1943. He had tried to enlist when war broke out, but was rejected because of an ulcer. Instead he offered his services to the Department of Information for which he made four short features (see Soldiers Without Uniform, c1941, Power to Win, 1942, A Mountain Goes to Sea, 1943, and While There is Still Time, 1941).

Forty Thousand Horsemen opened in Australia on 26 December 1940, after another dust-up with the Commonwealth Film Censor. It was a major hit in Australia and, in cut-down version, in the US and the UK. The Pacific war had not yet begun but Australians were fighting in the Middle East, where the film was set (during the Great War). In terms of timing, Chauvel could not have chosen a better story to tell. The film shows a huge leap in Chauvel’s confidence and technique, part of which comes from the third study period in Hollywood in 1936-37, and part from his access to more resources. Australians had never seen locally-made action sequences like the film’s final charge at Beersheba, both in terms of scale and violence. It was an example of Chauvel’s ingenuity, rather then simply more budget. During the NSW sesquicentenary celebrations in early 1938, he seized an opportunity to borrow a cavalry division for a day’s filming at Kurnell, south of Sydney, a full two years before production proper began on the film. He also benefited from the great depth of expertise at Cinesound, which he hired as his studio base. Chauvel had never had access to such competent technicians. Horsemen remains Chauvel’s best-loved film, partly because it made Australians feel proud of themselves. Chips Rafferty’s presence, in his first major role, was a major part of that success, playing a relatively new kind of Australian hero – the tall, laconic bushman soldier who was honest, steadfast and full of bush wisdom (see Forty Thousand Horsemen, 1940, clip two).

Rafferty and co-star Grant Taylor joined Chauvel back in the sand dunes three years later, to make The Rats of Tobruk, which I would argue is a better film about war than Horsemen. It’s dirtier, darker, less heroic, more graphic and closer to the lives of the soldiers. Both films were daring in the way they confronted audience expectations about death: in both films, two of the three main characters are killed in action, an example of Chauvel’s refusal to follow classical heroic storylines. The Rats of Tobruk (1943) is often described as an artistic failure, because of its clunky attempts at comedy featuring George Wallace, but its depiction of ground-level desert warfare – what was actually happening in the Middle East at the time – is very harrowing and less like propaganda than its predecessor.

Passion projects

Chauvel emerged from the war years stronger, more confident and with even greater ambition to produce films worthy of the passion he felt for Australia. The Chauvel legend reached its height in this period. Charles and Elsa Chauvel, who had had to conceal their close working relationship in the early 1930s, were now lionised as a kind of national couple, particularly in women’s magazines. In the renewed optimism of the postwar years, they were the attractive face of Australian nationalism, a hardworking couple intent on making feature films for the world, not just Australian audiences. The reality was somewhat different: Australian production after the war was almost non-existent. Greater Union declined an offer to join forces with Britain’s Ealing studios, and closed down Cinesound’s feature production, effectively ending the movie career of Ken G Hall. Chauvel had written to wartime Prime Minister Ben Chifley suggesting the government put up half of the money to make Australian features, but got nowhere. Worse, when Robert Menzies became prime minister in 1949, he actively dissuaded feature production. In the last 15 years of his life, Chauvel was able to make only two features, Sons of Matthew (1949) and Jedda (1955), and the TV series Australian Walkabout (1958). Even so, that was a remarkable achievement, given the times.

Sons of Matthew (1949) is still a controversial picture in Australian movie history. It was Chauvel’s most intensely personal project, a paean to white pioneering settlers in the region in which he grew up, but it cost four times more than any film he had made – £120,000. It has been argued that it cured Greater Union of any desire to participate further in Australian production, and contributed to the long fallow period which followed, during which virtually the only features made here were foreign–backed offshore productions. On the other hand, this may well have happened without Chauvel making Sons of Matthew (1949). He can hardly be blamed for Greater Union’s reluctance: they had long had reservations about high-risk Australian productions, when they could import films cheaply from elsewhere. Australian audiences greeted Sons of Matthew (1949) with rapture, but it was a long time before the film made a profit. The arduous filming in Queensland has become legendary, and it must have taken a toll on Chauvel, who already had an ulcer. Nevertheless, he continued to work on projects that were almost reckless in their risk-taking.

Jedda (1955) took three years to complete. It was in colour when Australia didn’t even have colour processing facilities. It was the first film to use Aborigines as main characters, but neither Robert Tudawali nor Ngarla Kunoth was a trained actor and nor were many of the supporting cast. To make this film in a healthy environment for feature production would have been difficult. Making it in the early 1950s, when the climate was actually hostile to film, was beyond heroic. And yet the Chauvels succeeded once again. Sons of Matthew (1949) and Jedda (1955) are two of Charles Chauvel’s greatest films, both expressions of his nationalist fervour as high melodrama. They were the last flowering, in feature production, of his remarkable energy and ambition. His last work was a major undertaking for television – a co-production between the BBC and the ABC, Australian Walkabout, in which he and Elsa Chauvel spent three years filming a 13-part Australian outback safari series. The series was shown on Australian television and repeated three times on British television. Charles Chauvel died in 1959, aged only 61, of coronary vascular disease, at his home in Castlecrag, Sydney.

Chauvel’s legacy

His legacy as an Australian filmmaker is still a matter of debate. In his early career, before Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), Chauvel was never much interested in naturalism. Some of his films may now seem very mannered in performance, but they would not have seemed so in their own times. He was a melodramatist, at a time when melodrama was much more popular than it is now. He was also polemical, which was unusual even then, so that his films are openly and heavily imbued with purpose. More than any contemporary Australian director, he experimented with form and hybrid, even as he drew closer to Hollywood classicism in his later work. He used documentary and drama together as early as In the Wake of the Bounty (1933), and as late as Jedda (1955).

While most other filmmakers started with a story or a character, Chauvel usually began with a place, a setting that he then researched until a story showed itself. His connection to landscape was deeper than any of his contemporaries and it drove him to extraordinary lengths, in search of backgrounds that would distinguish his films from those of any other country’s productions. He was both an internationalist and a nationalist – keenly aware of the rest of the world’s films and determined to be different. He created his own legend as the independent maverick producer, but he received more government assistance than any other producer, through carefully deliberate lobbying and cultivating of political power. His films were the first to receive international distribution in the USA and UK, but almost none was released intact in foreign markets. Jedda was the first Australian film invited to the Cannes Film Festival, but it was cut by 40 minutes for its UK release.

The remarkable thing about Chauvel is that he never gave up. He is said to have modelled himself on the great French director Abel Gance, who said ‘enthusiasm is everything’. Chauvel was Australia’s most personal director for the 35 years in which he was active, the first who can rightly be recognised as an ‘auteur’. Even now there are few who come close to his commitment and vision – to make films about Australia, almost exclusively.

External Links

- Chauvel, Charles Edward, Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Chauvel Cinema, Along the movie trail with Chauvel

- General Sir Henry George Chauvel, Australian War Memorial

- Jedda, National Film and Sound Archive

- Official Selection 1955, Cannes Film Festival

Citations

- Charles and Elsa Chauvel: Movie Pioneers (1989)

Carlsson, Susanne Chauvel

Publisher: St Lucia : University of Queensland Press ISBN 0702222518 - My Life with Charles Chauvel (1973)

Chauvel, Elsa

Publisher: Sydney : Shakespeare Head Press ISBN 0855580623 - Featuring Australia: the Cinema of Charles Chauvel (1991)

Cunningham, Stuart

Publisher: Sydney : Allen and Unwin ISBN 0044422547 - Directed by Ken G. Hall: autobiography of an Australian film-maker (1977)

Hall, Ken G

Publisher: Melbourne : Lansdowne Press ISBN 0701806702 - Australian film, 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production (1998)

Pike, Andrew and Ross Cooper

Melbourne: Oxford University Press ISBN 0195507843 - Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (1989)

Shirley, Graham and Brian Adams

Sydney: Currency Press ISBN 0868192325

- Titles

- Portrait

- Extras

- Screenography